PROGRESS: Floyd Collins remembered a century on

Published 6:00 am Friday, March 28, 2025

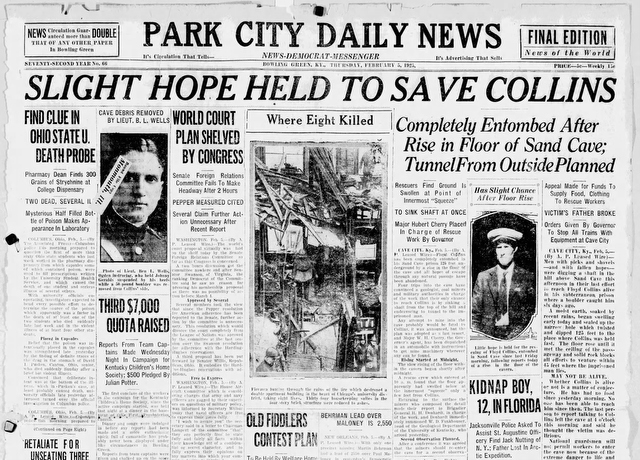

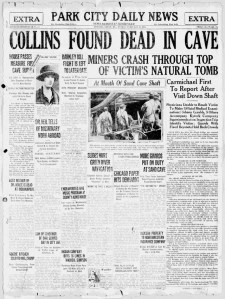

- The Thursday, Feb. 5, 1925 edition of the Daily News, featuring coverage of Floyd Collins as rescue attempts continue in Cave City.

For the two weeks Floyd Collins spent trapped inside a southcentral Kentucky cave, it’s unlikely he ever thought his story would live on a century into the future.

However, the 100th anniversary of his death inside Sand Cave has brought with it numerous tributes and even a musical chronicling his life.

Floyd Collins (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Kentucky’s cave systems in the early 20th century were at the forefront of a period of conflict known today as the Kentucky Cave Wars. Before the area was designated as Mammoth Cave National Park in the early 1940s, many caves were privately owned, with owners each charging admission for visitors and running their own tourism businesses.

Trending

The roots of the cave wars trace back to the late 1800s, when attractions such as Diamond Caverns opened just before the Civil War broke out, according to the National Park Service. Cave-owning was seen as a very lucrative business, since the area’s rocky soil discouraged many from farming. More than 20 caves were open to the public by the early 1920s, according to NPS.

It was during this time that Collins first began exploring underground. Collins’ family owned Great Crystal Cave, a cave Collins himself discovered on the family’s farm in 1917.

Collins began to commercialize the cave, with the Daily News running classified ads for it regularly in 1921, ads describing the site as “the latest and most wonderful discovery” in the area.

Great Crystal Cave, a cave discovered by Floyd Collins in January 1917. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Business for Great Crystal Cave was tough. NPS reported that to be a successful cave operator at that time, you either had to have a cave located along a roadside or you had to hire “cave cappers,” – solicitors who would stand on the side of roads providing cave information to travelers.

The Collins family had neither.

Floyd Collins set out to remedy his family’s situation by finding more caves that could grow the business. One of these was known as Sand Cave.

Trending

Collins entered Sand Cave on Jan. 30, 1925. Located along the Cave City Road, the 35-year old Collins was attempting to widen a portion of the cave when a large stone was dislodged and fell onto his leg, pinning him 200 feet underground.

NATIONAL SENSATION

A person looks at headlines hanging in a window from the Louisville Herald-Post carrying stories over ongoing rescue attempts for Floyd Collins. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

The news of Collins’ entrapment spread around the country, with newspapers coast to coast updating readers each day Collins was trapped.

The first story the Daily News carried on Collins’ entrapment was an Associated Press piece which ran on Feb. 2, 1925. The AP said that Collins’ brothers Homer and Marshal were offering a $500 reward – almost $9,000 in today’s money – to anyone who could enter the cave and bring Floyd Collins out alive.

However, the AP reported that no methods tried to that point had worked.

“Every experiment had been tried, only to fail,” the AP reported. “Every suggestion had been considered, but none proved helpful.”

Kentucky Gov. William Fields also tried to find a solution. Upon Fields’ request, a Louisville & Nashville train was dispatched to Cave City carrying on board an “expert driller and engineer.”

The AP story states Collins had been discovered underground the Saturday before, roughly 24 hours after he first ventured into the cave. By Feb. 2, Collins’ third day underground, the AP reported his strength was “slowly ebbing.”

The story states that Collins was using his remaining energy to direct a group of workers who had been drilling into the boulder pinning him down. By that point, crews had been at work for more than 40 hours.

Though Collins was trapped in the cave, he was not entirely inaccessible. Rescuers were able to get food and water to him, but the rock pinning his leg could not be moved.

The passage to him was narrow as well. One 10-foot section of the passage was only eight inches high.

Collins appeared to a reporter to be in a “stupor.” His hands appeared swollen and an oil cloth covered his face to keep rainwater off. The rock pinning him down was estimated to be about eight feet across.

The following day, the Daily News devoted its lead story to Collins with the headline “Every Effort to Release Collins Prove Futile.”

According to AP reporting, the crew of stoneworkers from the Louisville Monument Company who were attempting to chisel away the rock pinning Collins down were getting ready to leave the site, saying their services had been declined by the Collins family.

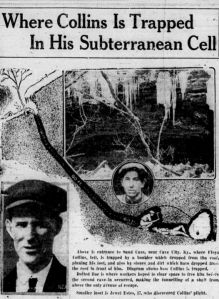

A 1925 Daily News graphic showing how Floyd Collins was trapped in Sand Cave.

By now, Collins had been underground for around 100 hours. Small pieces of rock were falling on Collins and groans of pain could be heard through the cave.

In Smiths Grove, 33 National Guardsmen and three officers were on standby, ready to go to Cave City to either provide help with the rescue or maintain order around Sand Cave.

Rescue efforts at the scene were unorganized, the AP said, although Collins remained optimistic about leaving the cave. The AP reported that about six empty bottles had been found in the cave that contained coffee and food items, dropped into the cave by passersby. According to the AP, Collins had asked his brothers to bring him “a gallon of milk and some stewed onions.”

The AP stated that over four days, Collins had only moved five inches.

As the days wore on, reporters were able to get close enough to Collins for interviews. Speaking to Courier-Journal Reporter William Burke “Skeets” Miller, Collins shared his experience in the cave.

“ ‘Surely,’ I thought, ‘no man was ever trapped like this,’ “ Collins told Miller. “I prayed as hard as I could.”

Miller’s small stature allowed him to access Collins underground. Collins told him the Saturday after he got stuck in the cave his brothers came down to try to help, without success. As attempt after attempt failed to free him, Collins said he started losing confidence.

“I prayed continually,” Collins told Miller. “Sometimes I would be in a stupor. I could hear people coming in, but they seemed far away. I could hear voices, but I could not remember what was said. Sunday night I slept some. I dreamed of angels and I awoke praying.”

Miller eventually won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the Collins saga.

By Feb. 5, hope of rescuing Collins was running out and efforts became more desperate. Gov. Fields ordered all trains carrying equipment to stop in Cave City and appeals were made to provide supplies for rescue workers.

Rainfall into the cave caused the ground to swell, completely closing off the original entrance. A group of military personnel, coal miners and a geologist determined at this point their only hope of reaching Collins was to dig a new tunnel into the cave.

This idea was chosen as a “last resort,” since it was believed that any mining into the cave would likely kill Collins. That is, if he wasn’t already dead.

“He has had no food since yesterday morning,” One Feb. 5 news report stated. “No one has been able to reach him since then.”

There was still some optimism. Lee Collins, Floyd’s father, was hopeful that his son could hold out until a new shaft was dug, which would take about two days by one estimate.

Before the groundswell, electrical pads had been installed around Collins to keep him warm and a lightbulb had been lowered down to provide additional warmth and light for him.

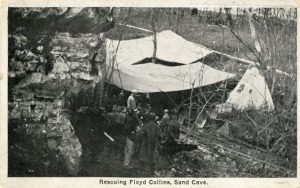

Tents and rescue workers stand at the mouth of Sand Cave in this postcard photo as cave explorer Floyd Collins is stuck below, pinned by a rock that fell onto his leg. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

The story of Floyd Collins was among the first widespread media sensations in U.S. history. Countless media outlets sent staffers to Cave City to report each day on Collins’ entrapment, and the story was one of the first of its kind to be reported on by radio.

The Daily News reported that A.M. Causey, the local manager of Bowling Green’s Western Union Telegraph office, was traveling to set up a field office in Cave City for use by the nation’s media.

Newspapers would often have their written reports transported from Cave City by air couriers. One of these couriers was a then-unknown pilot named Charles Lindbergh, who flew news dispatches and photographs of the scene to Chicago.

By one account, the Chicago Tribune was receiving 4,000 calls per day from readers looking for new information on Collins.

All of the media attention drew spectators and skeptics. As the days wore on, some argued that the entire story was a hoax.

This rumor got so bad that at one point Bowling Green native and Kentucky Lt. Gov. Henry H. Denhardt, who was commanding National Guard troops in the area, was ordered to convene a military court that would determine if Collins was indeed stuck in the cave and why rescue efforts weren’t working.

“It is my purpose to determine exactly why the efforts to rescue Collins through the natural passage failed,” Denhardt told the press.

Other rumors suggested that Collins was indeed inside the cave but, when he heard rescuers approaching, he would “climb into position.” When they left, he would climb out and go to a secret supply cache. The military court found that none of these rumors were true.

Gen. Henry H. Denhardt (left) speaks with a miner as efforts to rescue Floyd Collins continue in Sand Cave. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Work on the shaft continued and on Feb. 8, 1925, an estimated 10,000 people flocked to Cave City on what would become known as “Carnival Sunday.” This was the day many believed Collins would finally be lifted out of the cave. The atmosphere in Cave City took on a carnival-like atmosphere with food, entertainment and prohibition-era booze abounding.

Collins was not rescued that day, and he spent roughly another week below ground before death came. Collins’ body was discovered on Feb. 16, although it’s believed he passed away a few days prior. Current estimations place Feb. 13 as the day of his death.

Collins’ remains were discovered after a group of miners wound up in the natural passage of the cave after the limestone they were on collapsed. None of the physicians on site were able to enter the cave for a medical examination.

However, based on reports gathered by those who were in the cave, the cause of Collins’ death was likely exhaustion and starvation.

Even with his body still underground, Collins’ funeral was held on the surface on the afternoon of Feb. 17, led by the Rev. C.K. Dickey of the Cave City Methodist Episcopal Church. As hymns were sung, boulders were placed back at the mouth of Sand Cave, sealing Collins’ body within.

The front of the Feb. 16, 1925 edition of the Daily News, announcing the news that cave explorer Floyd Collins had died after roughly two weeks stuck underground after a rock fell and pinned his leg inside Sand Cave.

“Everything has been done that could have been done and man’s ingenuity and modern machinery have failed,” Collins’ father Lee Collins told the press. “No more lives should be sacrificed in further attempts to remove his body.”

Though Floyd Collins was intended to rest in the cave, others had different plans. Two months after his funeral, Homer Collins hired a team of workers to exhume his body. After several days of digging workers were able to move the stone from Collins’ body and lift him out of the cave.

Collins was buried for the second time on April 26, 1925, on his family’s land. Collins’ grave was on a knoll overlooking the Great Crystal Cave he discovered years prior.

Collins rested here for around two years until Lee Collins sold the homestead and the Great Crystal Cave to Dr. Harry Thomas. Thomas, presumably sensing the tourism draw Collins was, exhumed his casket and placed it inside Crystal Cave.

In June 1927, the Daily News reported that a legal fight was breaking out between Thomas and Homer Collins. Homer opposed the “commercialization of his brother’s body” and, with his surviving brothers, was seeking $50,000 in damages from Thomas, over $900,000 in today’s money.

This suit was nullified after officials found that the entrance to Sand Cave was just over the county line into Hart County, not in Edmonson County, where the suit was filed.

Thomas was later indicted by a grand jury in a separate case for moving Collins’ body out of the grave, an act the indictment described as “mutilation of the grave of Floyd Collins.” Thomas won an acquittal in Edmonson County Circuit Court in March 1928.

On March 19, 1929, Collins’ body was stolen from the Great Crystal Cave. That same day, law enforcement found Collins’ body wrapped in burlap lying on the banks of the Green River, a few hundred yards from the entrance to the cave.

Upon discovery, investigators found that Collins’ leg was missing – the one that had been pinned under the rock in Sand Cave more than four years prior.

The Collins family continued fighting Thomas for rights to the body, though later courts ruled the corpse had to stay in the Great Crystal Cave.

Collins’ body remained available for public viewing in the cave until 1948, when it was moved to a secluded corner of the cave to dissuade any future looters. Collins’ remains were kept inside a chained casket.

In 1961, Mammoth Cave National Park purchased the Great Crystal Cave for $285,000 and closed the cave permanently to the public. Upon the wishes of Collins’ descendants, his remains were removed from the cave, a process which took over two weeks.

FINALLY PUT TO REST

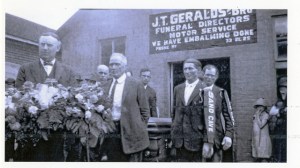

Pallbearers carry the remains of Floyd Collins out of a funeral home following services. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Sixty-four years after he died, Collins was finally laid to permanent rest on March 24, 1989, in the cemetery at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church after a private, 40-minute service attended by around 60 people.

For a time, many thought the saga of Floyd Collins was finally over. However, fascination with his story is still around. Many books have been written since Collins’ story began.

As 2025 marks one century since Collins’ entrapment, across southcentral Kentucky different commemorative events are on the books this year, including the musical Floyd Collins, which was performed at the Southern Kentucky Performing Arts Center.

Leticia Cline, a Cave City native and Floyd Collins’ great-great-niece, told the Daily News the story of her great-times-two uncle is a source of pride for her and her family.

“It says a lot about our people, like the struggle and the stubbornness to do what we believe in,” she said. “And I think that that’s a rare quality.

“I think it’s a story that needs to be told, and I’ve always been shocked my whole life that it’s not bigger than what it is,” she said.

A young descendant of cave explorer Floyd Collins walks past Collins’ casket at a small funeral service in 1989 at Mammoth Cave Baptist Church. (WKU SPECIAL COLLECTIONS)

Having grown up with Collins’ story, Cline said it got “cooler and cooler” as she got older. Cline has researched the story herself and, without sharing too many details, said she is currently writing a book on the subject.

Cline believes the continued interest in the story comes from all of the layers to it, ranging from the rescue attempt to the five different burials Collins had, to the national reach the story of his entrapment had.

“ … Just knowing that it was our region, a tiny speck on the earth, and that many people were fascinated with it, it’s all (a) good story,” she said. “It’s all good storytelling.”

David Lee, a retired professor of history at Western Kentucky University and the former university historian, said Floyd Collins’ story taps into “such primal fears.”

“It’s a horrible story on so many levels, but I think it does tap into some basic human fears that we all would easily have,” he said. “Panic, the fear of death, the sense of total isolation, it’s just a deeply unsettling story.”

Lee believes this is where much of the continued interest comes from. Additionally, he notes the fascination around stories of ongoing rescue, comparing it to the 2018 rescue of a team of soccer players from a flooded cave in Thailand and even the story of the ill-fated Apollo 13 mission.

“In all three of those cases, a fundamental question is ‘have human beings gotten themselves to some place that there’s no way to get them back from,’ ” Lee said.

The grave of famed cave explorer Floyd Collins at the Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery. (WES SWIETEK / Daily News)

Today, Floyd Collins rests in the Mammoth Cave Baptist Church Cemetery, in a plot located beneath some oak trees and next to his mother. An inscription carved on the bottom of the stone sums up his life:

“Trapped in Sand Cave Jan. 30, 1925.

Discovered Great Crystal Cave Jan. 18, 1917

Greatest cave explorer ever known.”