Schools add interpreters, translators

Published 12:15 am Thursday, January 14, 2021

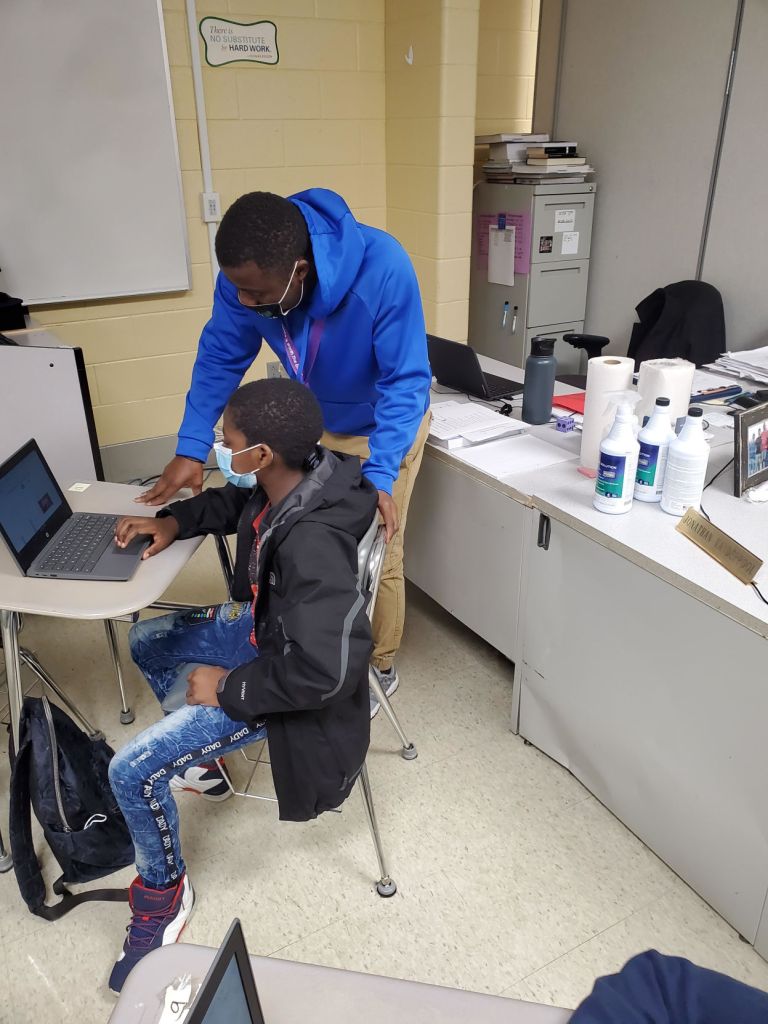

- Wilondja Ramazani helps a student in the Bowling Green Independent School District.

A new grant has enabled local schools to add interpreters, translators and program coordinators to work with their refugee student populations.

Dee Anna Crump, director of English learner and federal programs at Warren County Public Schools, said WCPS will use the grant to employ two refugee program coordinators.

The grant was made possible by Catholic Charities of Louisville, the archdiocese’s social-service arm.

The staffers – Sharon Sinarahua and Speciose Nyiramana – will work with school staff, parents and students to “remove barriers to learning that these students might be experiencing,” Crump said.

More than 1,000 WCPS students are refugees, Crump said.

Crump said both coordinators are fluent in either Spanish or French, Kirundi and Kinyarwanda, the last three of which are spoken by many of the district’s African refugee families, which represent a growing demographic in Warren County.

Under President Donald Trump, national refugee arrivals dipped to historic lows. However, under President-elect Joe Biden, WCPS expects those arrivals to increase again, Crump said.

“We expect that, given a little bit of time, our numbers will increase again,” Crump said. “We just know that these families need a lot of support” to do well in school and access the resources their families need.

In the Bowling Green Independent School District, where there are about 160 refugee students, the grant is paying for two Swahili speakers: Therence Nsabiyuba and Wilondja Ramazani.

Both work as interpreters and translators supporting students and teachers in the classroom, said Elisa Beth Brown, BGISD’s director of elementary and secondary programs.

Last summer, when the district hired Nsabiyuba and Ramazani, Brown said the two were indispensable and had a “tremendous impact” in registering Swahili-speaking students for school in the middle of a pandemic.

Brown said Nsabiyuba and Ramazani are working at the district’s middle and high school. They’re working with refugee students there who may not have formal schooling or who have had their education disrupted by the persecution they faced in their homeland.

“When you come in the sixth grade or higher, and you are expected to perform as your peers do – but you don’t speak any English – the need is terribly great for them to be supportive,” Brown said of the interpreters.