Heavily redacted WKU sexual harassment records reveal misconduct

Published 12:15 am Sunday, June 13, 2021

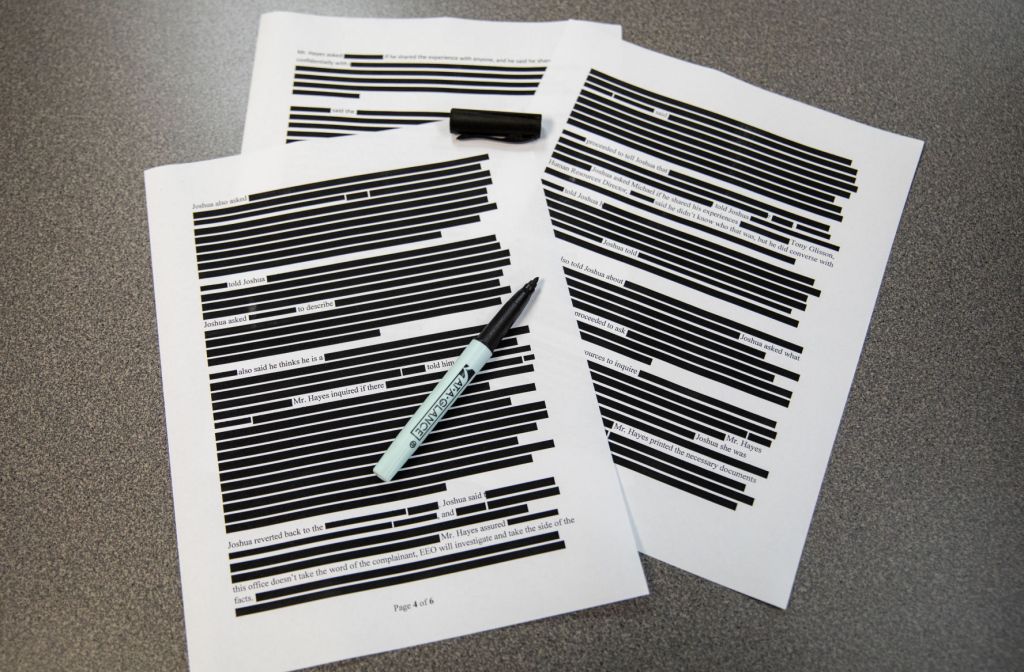

- The heavily-redacted WKU Title IX sexual misconduct records are shown after being obtained by the Bowling Green Daily News via an Open Records Request. (Photo illustration by Grace Ramey/photo@bgdailynews.com)

Heavily redacted records documenting sexual harassment committed by Western Kentucky University employees reveal numerous instances of misconduct that resulted in faculty and staff being allowed to quietly leave their jobs or retire. And in some cases, those who knew about the transgressions failed to report them – even when students came forward to complain.

The newly released – though heavily blacked out – employee sexual misconduct and harassment records are the result of an Open Records Act request that a student journalist with WKU’s College Heights Herald placed in November 2016.

The reporter, Nicole Ares, asked for documents of Title IX investigations into faculty and staff sexual misconduct against students that spanned the previous five years, and she made the same request of every public university in the state.

Six universities complied with Ares’ request, redacting the names of students and their identifying information.

Ares’ award-winning report – “In the Dark: Records Shed Light on Sexual Misconduct at Kentucky Universities” – found that many university faculty from across the state who were accused and ultimately found to have committed acts of sexual misconduct were allowed to quietly leave their jobs or stay with just a slap on the wrist.

Only two schools – Western Kentucky University and Kentucky State University – outright refused to hand over the records to Ares, with or without redactions.

The following year, in 2017, WKU sued its own student newspaper to keep the records out of the public eye – even after then-Attorney General Andy Beshear found that the university failed to adequately explain why it was denying the request.

Beshear ruled at the time that WKU must allow immediate access to the records – with the exception that the names and personal identifiers of complainants and witnesses be withheld.

In March, after a Kentucky Supreme Court ruling on a similar lawsuit between the University of Kentucky and its student-run newspaper, WKU said it would provide to the College Heights Herald “documents related to all Title IX investigations asserted against WKU employees from November 2011 to November 2016.”

WKU has maintained that federal privacy law prevented it from “releasing information which could lead to the identification of complainants.”

“We made it clear that we would follow legal precedent, and this ruling provides much needed additional clarity,” Andrea Anderson, WKU’s general counsel, said in a statement at the time. “Our focus from the beginning has been on protecting the identity of those filing the complaints. We look forward to bringing the litigation with the Herald to resolution.”

The Daily News obtained and reviewed its own copies of the heavily redacted WKU employee sexual misconduct and harassment records through its own Open Records Act request.

The substance of the records

In most cases – though not all – the names of employees accused of sexual misconduct or harassment were redacted.

“The names of the respondents are not redacted in the cases in which there was a finding of a policy violation,” Anderson wrote in an email to the Daily News.

However, a Daily News analysis found that, in at least two case files, the names of two WKU employees who were accused of misconduct remained unredacted.

The Daily News is not disclosing the names of these individuals because the university ultimately found that a policy violation had not occurred in both cases.

There are, however, five case files in which the names of the accused employees were intentionally left unredacted and a violation was found to have occurred.

Anderson confirmed Friday to the Daily News that four of the individuals are no longer employed at WKU. The fifth employee was allowed to retire from the university, according to his case file, and a Daily News obituary states that someone by that name died last year.

The five individuals are:

Michael Kallstrom – Female students complained that Kallstrom, a university distinguished professor in WKU’s Music Department, subjected them to inappropriate touching, comments and looks. During one such occasion, when a student was visiting Kallstrom’s office and was accompanied by a male student, Kallstrom grabbed the female student’s thigh when the male student turned his head to take a phone call, the records said. “The Anonymous Complainant said as soon as she walked out of Dr. Kallstrom’s office she told her friend what occurred, but he said he did not witness it.” The student also recounted another episode during which she wore a T-shirt and Kallstrom told her “if it was lower cut, it would look better,” according to the investigation documents.

After speaking with more than 20 witnesses, the university’s investigator wrote that “due to the numerous reports of inappropriate physical contact from witnesses interviewed and inappropriate comments mentioned, the corroborating evidence is overwhelming.” Kallstrom was found to have violated university policy, and he longer works at WKU. However, the investigation revealed that the student who brought forward the complaint told at least three faculty members of Kallstrom’s behavior before the university began its investigation. The conclusion of the investigation found that “some of the faculty chose not to report their meeting(s) with the Anonymous Complainant to the Title IX Coordinator, a Deputy, and/or one of the Investigators.” Every employee at WKU is considered a “responsible employee” and is required to report allegations of sexual misconduct and assault – especially those reported by students. The investigation found that several faculty members failed to live up to that responsibility.

Kenneth Johnson – Johnson first got the attention of WKU’s Title IX investigator in March 2014 when a student complained that “Mr. Johnson threatened to place a hold on her TopNet account, which would prevent her from registering for classes, if she did not stop by his office to visit him and/or have dinner.” Johnson had no authority to place a hold on the student’s account, the file said, but “before she discovered the truth, she agreed to have dinner with him. She specifically stated, ‘I had knots in my stomach. It bothered me how he used his position as a form of manipulation.’” The student told investigators that she knew of other students who had been coerced by Johnson, and that she once witnessed him having dinner with another student. Rumors about Johnson dating female students and having sexual relationships with them “were common,” the investigation said. Investigators also learned that “Kenneth has made negative remarks in front of others about a WKU male student potentially being gay, including while this student was also present.” The investigation found that Johnson did in fact violate WKU’s Standards of Conduct Policy and Discrimination and Harassment Policy, in addition to Title IX of the Educational Amendments of 1972. Johnson is no longer employed by the university, Anderson told the Daily News.

Colleen Donovan – Records show that WKU investigators found Donovan did violate university policy when she was employed as an academic readiness instructor at WKU. Although some of Donovan’s behavior is obscured by the university’s redactions, the investigation cites testimony from students that “on the first day of class, Ms. Donovan told the class that the highest grade each of the students would receive would be a C, except for one or two students who would receive an A or a B.” When one student arrived late to class and protested being marked absent, Donovan “yelled at her, began walking circles around her, and telling her that she (Donovan) was in charge of the class,” according to the records.

Donovan encouraged the student to drop her class, the student complained, and records show that the university also investigated the case as a possible instance of sex discrimination because the student was the only female in her class. The university was not able to prove that discrimination had occurred, however. Multiple students complained that Donovan refused to take their questions in class and to accept their work: “Colleen continuously rejects drafts of their papers, requests them to re-do assignments, but never accepts their work as final submissions,” the file states. Records make clear that administrators recommended disciplinary action be taken against Donovan, but they do not spell out exactly what kind of action, leaving that up to her unit and department leaders to decide. Donovan is no longer employed by WKU, Anderson confirmed Friday.

Steve Briggs – Briggs’ case file reveals that he was issued a verbal warning by his supervisor in 2013 “regarding your inappropriate touching of and comments towards at least one other employee.” It was a warning that Briggs allegedly failed to comply with, and in November 2014, he drew the attention of the university’s Title IX officials once more, earning him another warning – though this time it was written. In January 2015, he was notified that “these incidents – including your poor judgment and non-compliance with my prior directive – serve as the basis for this written reprimand. Any further incidents/complaints or violations of this nature will result in a recommendation for termination of your employment.” It’s unclear who sent the memo to Briggs because the person’s name is blacked out. As a consequence at the time, Briggs was required to undergo training to address appropriate workplace interactions. Briggs is no longer employed at WKU, the university’s general counsel confirmed.

Timothy Mullin – Mullin’s case file indicates he was allowed to retire (though it is not clear when because the date of his retirement memo is redacted) after complaints surfaced of him sexually harassing male students and belittling and berating the female employees he supervised. One female employee complained that “he has publicly humiliated me, habitually speaks to me in a condescending manner usually reserved for small children and animals.” The case file also documents Mullin’s behavior around male students: how he would openly stare at students’ behinds and make inappropriate comments about their appearance, according to the files. Another complainant stated that “Timothy Mullin is a lawsuit against WKU simply waiting to happen. If he remains employed by the university it is simply a question of when. If his serial sexual harassment of male students becomes public knowledge, it will result in irreparable harm to WKU’s reputation with students, parents and the community at large.” A Daily News obituary for a man by that name states that Mullin died in November 2020.

Despite those details regarding five individuals, the heavily redacted records obscure basic details of WKU’s misconduct and harassment investigations.

In total, WKU provided 17 case files to the College Heights Herald, spanning 1,896 pages of internal memos and emails, investigation notes and administrator interviews with the accused, witnesses and complainants.

Some records are so heavily redacted that the exact nature of the complaint – including the alleged misconduct – is obscured. In many cases, the personal notes investigators took are rendered unreadable, the contents of entire pages withheld.

Michael Abate, an attorney with the Louisville-based law firm Kaplan, Johnson, Abate and Baird who is representing the College Heights Herald, called the redactions “totally inappropriate” and, in his view, are a sign that the university is acting in bad faith.

“The only thing that should have been redacted from this is any specific identifying information regarding a student involved in the investigation,” Abate told the Daily News.

After the Kentucky Supreme Court decision in the case between the University of Kentucky and its student newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, Abate said he made clear to the university that only student names and identifiers should be withheld from the records.

Abate said he notified the university that the names of accused employees – regardless of the university’s finding in each case – should be disclosed to the College Heights Herald. He said he provided examples backed up by case law and opinions from various attorneys general on the matter to make his point.

“They utterly ignored that,” Abate said. “They did this knowingly without any justification, and it’s wrong.”

“In our view, this was not done in good faith,” Abate told the Daily News, calling the redactions “just a continuation of the culture that is totally adverse to transparency.”

Jon Fleischaker, also an attorney with Kaplan, Johnson, Abate and Baird, is credited with helping to draft Kentucky’s Open Records Act and said he found the extent of the redactions baffling and “extremely disappointing.”

Fleischaker called the sheer breadth of the redactions inappropriate and that they are not authorized by the state’s Open Records law that he helped author.

Speaking for himself and his wife, Kim – who have supported the university’s journalism program over the years with awards and endowed courses – Fleischaker condemned the university’s conduct in the case.

“We are extremely disappointed in the way that the administration at Western (Kentucky University) has handled” the records request, Fleischaker told the Daily News.

The purpose of Kentucky’s Open Records Act, Fleischaker said, is to dispel speculation and rumors and to promote government transparency and accountability with the clear light of day.

This case is not about any individual professor or administrator, Fleischaker said, but about how the university is comporting itself in sexual misconduct and harassment cases.

“Are they doing a good job?” Fleischaker said.

For his part, Abate anticipated that the matter would wind up back in court.

“We’re prepared to continue asserting the public’s right to know what happened,” Abate said.