Landmark game had Kentucky connections

Published 3:31 am Sunday, March 10, 2013

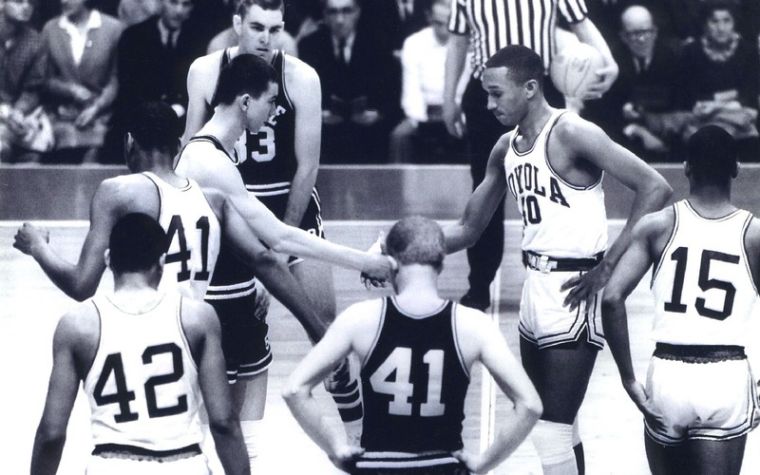

- Mississippi State's Joe Dan Gold, a Benton native, shakes hands with Loyola of Chicago's JerryHarkness before an NCAA game in 1963. The game paved the wayfor more colleges from the South to play against all-black teams. Submitted photo

It was 50 years ago this month, in March 1963, that a basketball game was played in the NCAA tournament that some believe was more socially significant than the 1966 Kentucky-Texas Western title game that led to the movie “Glory Road.”

The story of “Glory Road” was built around an all-white Kentucky team coached by Adolph Rupp against Don Haskins and his predominantly all-black squad from El Paso, Texas. The overly exaggerated movie script portrayed Rupp as a racist, which his players said he was not, and anyone who saw “Glory Road” quickly found themselves rooting for Texas Western. Larry Conley, a star on that UK team, said a while back that he was even pulling for the Miners when he saw the movie.

Trending

But enough about that.

Three years before that 1966 matchup, an NCAA game played between Loyola of Chicago and Mississippi State was equally telling. The story here didn’t have to be concocted to make audiences take sides. And the thread that is weaved through it all has a Kentucky connection or two.

Babe McCarthy coached Mississippi State, and it is well worth the time to explain how the legendary coach, who later coached the ABA’s Kentucky Colonels, even became a coach.

McCarthy attended Mississippi State as a student, and for the most part his only association with basketball was playing for his fraternity intramural team. Like most students at the time, he went to see some of the Bulldog games, usually to see the likes of Kentucky when they visited Starkville.

He coached a junior high team for a while before going to work as a salesman in the oil business. Then out of the blue came an opportunity to coach at his alma mater. Much has been written about McCarthy’s escapades at Mississippi State, but the bottom line as to why UK fans developed a hatred for him was that he was able to hold his own and then some against their beloved Wildcats.

Perhaps McCarthy’s finest hour came when he helped devise a plan after winning the SEC title in 1963 to get his team out of Mississippi in order to play against a predominantly all-black Loyola of Chicago team in the NCAA tournament in East Lansing, Mich.

Trending

The three-time SEC coach of the year defied an injunction that prohibited his team from going. But McCarthy, who had been ordered to turn down two previous NCAA bids, this time had the support of the school’s president, Dean Colvard, and athletic director Wade Walker.

State Sen. Billy Mitts, who had been student body president in his college days as well as a cheerleader at Mississippi State, led the efforts to block the school’s participation. With the backing of Gov. Ross Barnett, if Mitts had his way, McCarthy and his team would stay home.

But McCarthy had already set a diversion in motion so he could be conveniently out of reach when any official documents were delivered to the school.

First, Colvard was in Alabama on business.

McCarthy, Walker and a few others drove to Memphis, Tenn., and then flew to Nashville. At the same time, McCarthy sent his freshman team to the airport posing as the varsity. Meanwhile, the varsity was hiding out in a campus dorm room until the following morning, when they flew to Nashville on a private plane, where they hooked up with their coach.

Together, they all flew to East Lansing, where they lost to eventual NCAA champion Loyola 61-51. All was not lost, however, when the Bulldogs defeated Bowling Green State University and All-American Nate Thurmond in the regional’s consolation game.

This is where the Kentucky connection comes in. The captain of the Bulldogs was Joe Dan Gold, a forward from Benton in Marshall County. It had been assumed that Gold would play at nearby Murray State. However, McCarthy had latched onto the Kentucky boy and never let go.

Years later, Murray State Hall of Famer Bennie Purcell recalled that his school really wanted Gold, but he had committed to Mississippi State and stuck with it.

But there was Gold, with more than 10,000 fans watching and flashbulbs popping in East Lansing, shaking hands with Loyola All-American Jerry Harkness at center court just before the tip. It was a tipoff that led to many barriers coming down for college basketball in the South.

In 2007, I was doing a book signing with King Kelly Coleman at the boys’ state tournament in Rupp Arena. I sat down in a vacant seat while waiting for one of the games to end. Seeing one of the books about Coleman in my hand, the gentleman next to me asked me about it.

We talked for a while, and then he said, “I’m Joe Dan Gold,” and we shook hands. Of course I knew who he was and every time I asked him about his Mississippi State days and McCarthy, he would instantly start asking me about Coleman. “What is he doing today? What was it like interviewing him,” and on and on.

Gold had seen him play at Kentucky Wesleyan and had heard the stories.

But suddenly the game we were half watching was over, and so was our brief visit. Gold died in 2011, and I regret that I didn’t ever get to really know him.

When his funeral was held at Collier’s Funeral Home in Benton, a lone black man made his way toward the casket to pay his respects to the family.

It was Jerry Harkness.

The two had formed a bond over the years, even attending a reunion for the two teams back in 2008. But now here was Harkness, growing up as a kid in Bronx, N.Y., saying goodbye to Gold, the kid from Kentucky who he met on a basketball court some 50 years before.

Movie producers can say all they want about “Glory Road,” but the real basketball historians know the trip began in March 1963.

— Gary West’s column runs monthly in the Daily News. He can be reached by email at west1488@insightbb.com.