Book review: ‘Sweet Taste of Liberty’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 2, 2020

- BOOK REVIEW

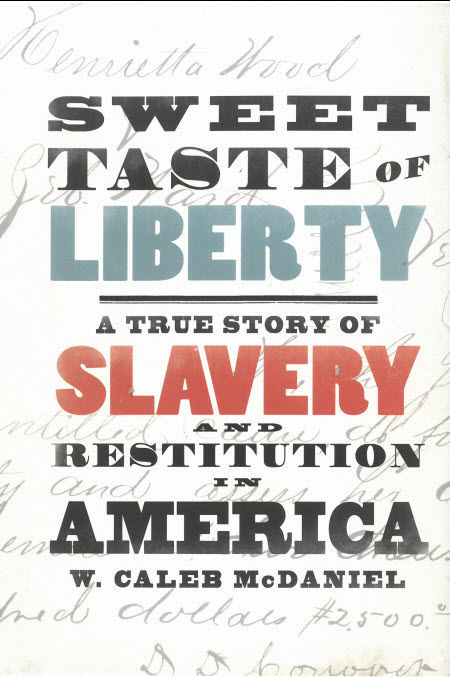

“Sweet Taste of Liberty: A True Story of Slavery and Restitution” by W. Caleb McDaniel. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. 340 pages, $27.95 (hardcover).

This book recounts the life of Henrietta Wood, a black woman enslaved in Kentucky in the mid-19th century. She was born a slave and became free before being kidnapped and reenslaved. Her reenslavement was the result of collusion between jaded, would-be inheritors, unscrupulous law enforcement officials, greedy employers, simple opportunists and willfully ignorant individuals seeking to profit. Like the thousands of other enslaved Kentuckians, she suffered and survived the pangs brought forth during her enslavement, including separation from her family, physical torture, derision for her plight and backbreaking labor. What makes Wood’s story unique, however, is her experience after bondage.

In 1878, Wood was awarded $2,500 for her enslavement, a sum worth $80,000 in today’s currency, and the largest amount awarded by a court to a formerly-enslaved person from a former owner. Many newspapers supported the verdict and were even unsatisfied with the meager amount awarded, only a fraction of the $20,000 Wood originally sought.

Still, many acknowledged that “Long Delayed Justice” had finally been served; even the New York Herald believed a precedent had been set, which would “be applicable to a great many cases yet untried.”

Wood originally filed a plea for trespass on the case, which allowed plaintiffs to sue when they had been harmed by later consequences initiated by the defendant, but was directed by the courts to amend the claim to simple trespass based on the use of force such as assault, battery or false imprisonment. The court’s decision in the end, however, awarded her compensation not only for her original kidnapping but also for afterward being “deprived of her time and the value of her labor” while reenslaved.

More than recounting Wood’s story, “Sweet Taste of Liberty” also offers implications into the contemporary question of reparations for slavery and racism. Here is an example of an enslaved person, who sued a former owner for unpaid labor. While court judgments criminalizing the activities of reparation leaders such as Callie House or dismissing suits because of limitations statutes stalled the movement for reparations in the 20th century, the initial reasoning legitimizing Wood’s case in the eyes of the court is still relevant. If the courts deemed one person suffered injustice during their enslavement, then induction would suggest that all enslaved people would have similarly suffered and similarly be deserving of redress.

In short, readable chapters, author W. Caleb McDaniel pieces together Wood’s life and those of her friends, family and captors from the scraps of artifacts left in the historical record – an interview with Wood, newspaper accounts of the kidnapping, slave owners’ diaries and partial court records. Researchers may find useful an essay on sources located at the end of the book, which details McDaniel’s investigation as well as the limitations of the primary sources he uncovered.

An excellent work of social biography and history “from the bottom up,” the author sifts through texts, often penned by literate white southern elites, to uncover the experience of the black underclass in the Civil War era and in doing so, resurrects the story of one formerly enslaved woman and the social forces that largely dictated the trajectory of her life.

There is ample discussion of individuals benefiting from Wood’s enslavement such as Lewis Robards, slave trader and one of Wood’s captors, Josephine Cirode, a former owner who eventually freed her, and Kentucky state legislator and warden of Fayette County jail Zebulon Ward, who previously conspired to sell her. There is also discussion of those who attempted to come to her aid such as John Joliffe, an abolitionist and lawyer who first represented Wood in a freedom suit in the 1850s, and Harvey Myers, another lawyer who eventually represented her in the civil suit after the Civil War.

But McDaniel pays equal attention to the experiences of the enslaved and free people whom Wood may have encountered. People such as Anthony and Ben, who like Wood were made to plant cotton in Mississippi’s Natchez district and later forcibly transported to Texas during the War. During their bondage, the pair was almost lynched for providing aid to a fugitive slave. Likewise, Wood may have known George Jackson, a recaptured runaway who had also been living independently in Ohio in the 1840s, but drew public attention when he was apprehended and forced to return to slavery in Tennessee.

Some of Wood’s story, however, will never be known. When was she born? Did she keep in contact when reunited with her brother, Joshua, after being sold and separated from one another for decades? What motivated her to pursue a civil suit for reparations even after being denied freedom in the 1850s after her reenslavement?

Because of the lack of available sources directly from Wood, her friends or her family, these questions, unfortunately, may never be answered. The book is divided into three sections, the first “the Worst Slave of Them All,” describes Wood’s early life as a slave and her kidnapping. The second portion details discovery of Wood’s wrongful captivity and initial judicial efforts to free her that ultimately fail. The book concludes with her reenslavement, her civil suit for reparations and her legacy, including the life and career of her son, Arthur Simms, who became a successful Chicago-based attorney.

Transpiring more than 100 years ago, Wood’s story nonetheless has ramifications for today. President Abraham Lincoln initially introduced an act to compensate southern slave owners for their loss of human property once national emancipation was enacted; but what if, instead, he had proposed compensation to the ex-slaves? How would such compensation have changed their lives?

McDaniel wanted readers to understand the link between reparations and black social mobility, so he chose to devote a substantial portion of the book to its discussion and that of Wood’s son, Arthur, who after being born a slave was able to become a homeowner, attend law school and join the small number of black Americans able to reach middle-class status before the 1960s, in part through the money awarded to his mother. While irrational and racialized stereotypes often portray reparations in the form of individual white Americans having to collectively pay black Americans money, only to be frivolously spent, fills the public perception of reparations, such scenarios are misplaced. Many have written about the value of education, community resources, tax breaks, home loans and other incentives which could take the form of reparations for enslavement and its legacy. However, for any of these examples to be tested, they must first be discussed.

Henrietta Wood was an enslaved, illiterate, aged, black woman who had the audacity to demand what she was owed. It is a testament to this nation’s character and potential that what she was owed was finally rendered to her.

The small settlement was little more than an insult to Zebulon Ward, who had become wealthy as a slave owner before the war and continued to earn profits by exploiting freedmen in the convict lease system after its conclusion. This settlement, however, and the investment capital that it entailed, changed Wood’s life. Wood’s case is exceptional in so far that she successfully received reparations, but the fact that she was owed for her labor and the latent harms that her enslavement caused her children is not unique; it is the same for all enslaved people and their descendants. If such a settlement had the effect of lifting Wood and her progeny out of the common trap of generational poverty, imagine what it could have meant to the economic potential of the millions of enslaved black Americans and their offspring, most of whom lived for generations in poverty and would not reach middle-class status until the second half of the 20th century.

Reparations for black Americans is not meant to take away from the struggles of all Americans, including free immigrant laborers and poor whites, who have suffered hardships under unfair laws and indifferent governments. Yet, it must be understood that these injustices are fundamentally different from the systematic racism against people of African descent embedded for hundreds of years into American society. The United States should acknowledge its complicity in depriving black people of liberty and it should apologize for it. Only after this national awakening occurs will discussion of reparations not be met with ridicule and just as importantly productive public conversations about the nation’s racialized history can be had. In telling the story of Henrietta Wood, McDaniel has contributed immensely to this nation coming closer to this goal. Researchers, leisurely readers and those in the general public looking to be more informed about the history of slavery and reparations in this country, would be hard-pressed not to find this book compelling. It is a story that deserves to be heard and a conversation that needs to be had.

– Reviewed by Selena Sanderfer Doss, Western Kentucky University History Department.