Book review: ‘The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, April 24, 2022

- BOOK REVIEW

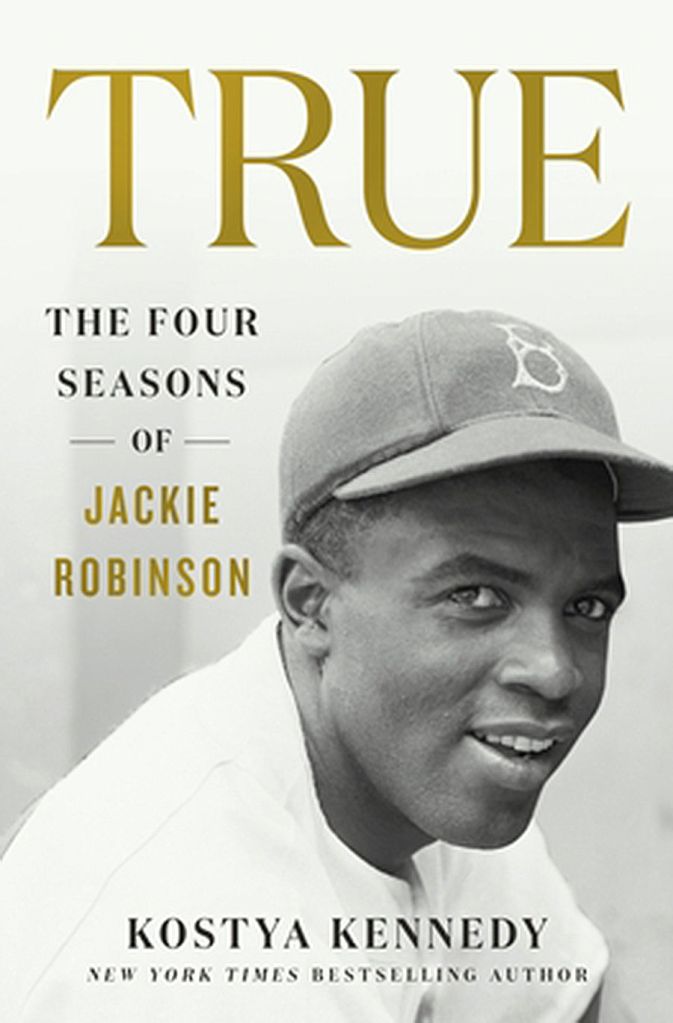

“True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson” by Kostya Kennedy. St. Martin’s Press. 278 pp. $29.99. Review provided by The Washington Post.

By October 1972, Jackie Robinson no longer moved in powerful bursts. His eyes were failing. His hair had gone white. For a quarter-century, Robinson had sought to represent the best of America, and when he threw out the ceremonial first pitch before Game 2 of the World Series, he looked worn by the burden.

Yet during the pregame ceremony honoring baseball’s Black pioneer, Robinson crackled with his old energy. After all the tributes, he took the microphone. “I’m extremely proud and pleased to be here this afternoon,” he concluded. “But I must admit that I’m going to be tremendously more pleased and more proud when I look at that third base coaching line one day and see a Black face managing in baseball. Thank you very much.”

He was a crusader until the end. Nine days later, Robinson died of a heart attack. In his final public appearance, he had again spotlighted the biases that plagued the nation, including in sports, and demanded better.

It has been 50 years since Robinson’s death and 75 years since his electric debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, when he became the first African American player in the modern history of Major League Baseball. It is comfortable, perhaps, to freeze our appreciation for him in 1947, when he endured racist abuse with stoic dignity. But the true Robinson should make us a little uncomfortable. He was a ball of pulsating tension, a man of fierce independence, a voice for genuine freedom. As Martin Luther King once wrote, “He incessantly raises questions to sear America’s conscience.”

Kostya Kennedy’s “True: The Four Seasons of Jackie Robinson” is the latest addition to the literature on this American icon. A former writer at Sports Illustrated and an author of books on Joe DiMaggio and Pete Rose, Kennedy brings literary grace to his subject, illuminating Robinson’s sizzling style on the ballfield, his colossal significance in American culture, his complex humanity and his enduring legacy.

Unlike a traditional biography, “True” focuses on four distinct years in Robinson’s life. Kennedy starts in 1946, Robinson’s single season in the minor leagues with the Montreal Royals. He then jumps to 1949, when the Dodger star glowed brightest, capturing the National League’s most valuable player award. In 1956, Robinson retired after a rocky season that included feuds with management and long stints on the bench, as well as glorious glimpses of his unique greatness. The book ends in 1972, with Robinson as a lion in winter, slowly fading, still fighting.

Kennedy’s approach allows him to linger over scenes, painting lush portraits of telling moments from Robinson’s career. He depicts how Jackie and his wife, Rachel, drew sustenance from their stint in Montreal, where local fans gave friendship and comfort. He portrays how Black fans cheered their hero with a deep, almost spiritual pride. He renders the everyday indignities and terrifying death threats during spring training in the Jim Crow South.

Some vivid passages describe Robinson on the base paths, showcasing his astonishing physicality and attacking philosophy. “None of Robinson’s contemporaries displayed his ability to start and stop and start and stop and start again, to jink his way past fielders and potential tags, to rattle and embarrass and elude,” Kennedy writes. “He would hover at times and then explode. For Robinson, each time on base promised an essay into new possibilities.”

At his best, Robinson dominated every facet of the game. During his 1949 MVP season, he led Brooklyn to the pennant while hitting .342 with 16 home runs, 38 doubles, 12 triples and 124 RBI. He stole 37 bases, scored 122 runs, turned 119 double plays and laid down 17 sacrifice bunts.

At this same time, Robinson was invested with enormous political significance. More than a celebrity under a magnifying glass, he had to represent an entire race. In 1949, after singer-activist Paul Robeson questioned whether African American soldiers would fight against the Soviet Union, Robinson testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, both affirming Black patriotism and blasting racial injustice.

Robinson lived in paradox. He was worshipped as a hero and disdained as just another second-class citizen. He injected baseball with audacious exuberance, yet suffered from excruciating pressure. His Dodgers proved the success of racial integration, winning six National League pennants, but lost five World Series to the New York Yankees. When the Dodgers finally triumphed over their hated rivals in 1955, Robinson watched from the bench, mired in injuries and slumps.

Kennedy fleshes out a proud, sincere and often stubborn man, especially in the final section. There is sweetness in Jackie’s devotion to Rachel, and there is tragedy in the saga of his son Jackie Jr., who overcame drug addiction and then died in a car accident. There is steeliness in Robinson’s political commitment, which included fundraising for civil rights organizations, campaigns with politicians of both parties and newspaper columns that criticized anyone who deserved it. There is an elegiac quality as Robinson makes his final rounds, burying some lingering resentments and asserting his place as baseball’s conscience.

The episodic structure of “True” has costs, as it bypasses some significant periods and themes in Robinson’s life. Most obviously, Kennedy pays minimal attention to the barrier-breaking integration of the Dodgers in 1947. He devotes little space to Brooklyn’s World Series futility or the franchise’s 1957 move to Los Angeles. Kennedy also might have explained that as one of the most important Black Republicans of his era, Robinson championed a progressive, patriotic political vision that got lost in the tumult of the 1960s.

“True” nevertheless explains Robinson in striking, human terms. Throughout the book, Kennedy sprinkles in the tale of Ira Glasser, a Jewish boy who grew up in East Flatbush and idolized Robinson. His fandom imparted subtle lessons about justice and equality. Glasser grew up to lead the American Civil Liberties Union. “We incorporated more than his style of play,” he wrote to Rachel Robinson upon her husband’s passing. “To us, baseball was a metaphor of life.”

– Reviewed by Aram Goudsouzian, who is the Bizot family professor of history at the University of Memphis. His books include “King of the Court: Bill Russell and the Basketball Revolution.”