Book review: ‘The Boston Massacre’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, May 31, 2020

- BOOK REVIEW

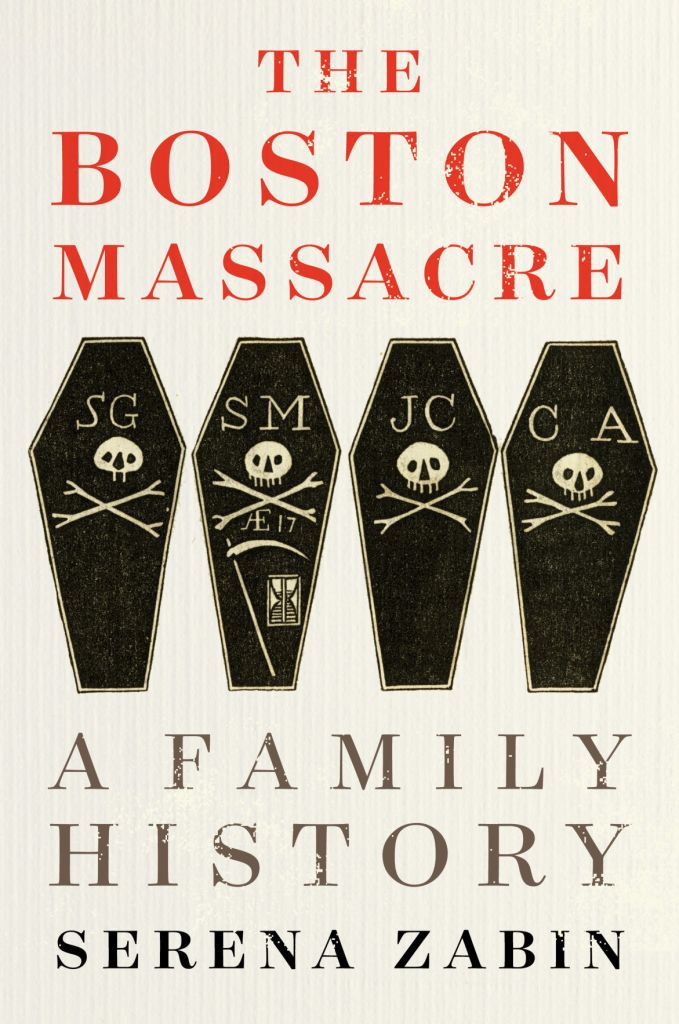

“The Boston Massacre: A Family History” by Serena Zabin. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 296 pp. $30. Review provided by The Washington Post.

Historians continue to assess the meaning of the American Revolution. But at first glance, what can one possibly say about the Boston Massacre that is new? The iconic event, immortalized 250 years ago in a famous engraving by Paul Revere, has been studied and written about exhaustively. The facts are well-known, even if interpretations have differed.

Trending

On a wintry night in 1770, British soldiers fired into a crowd of civilians, killing five men. While Revere’s print sought to portray the Bostonians as innocent victims, future President John Adams mounted a defense of the soldiers in court that underscored their helplessness in the face of an aggressive crowd. By emphasizing the notion of a confrontation between two separate camps, both versions concealed the intimate ties that existed between soldiers and civilians.

Through exhaustive sleuthing in British military records, official correspondence and Boston archives, Serena Zabin, a history professor at Carleton College in Northfield, Minn., changes this familiar story into a familial one. The result is a lively gem of a book that expands our views of early-modern military life, pre-revolutionary Boston and, in turn, the American Revolution.

Early modern armies were full of women. Married to privates and officers, they cooked, cleaned, nursed and laundered for soldiers while raising children. Though often derisively dismissed as “camp followers,” they provided crucial support. In recognition of their importance to the functioning of the army, many received rations, pay and even transportation when regiments got deployed. The 2,000 British regulars sent to Boston in 1768 to exercise riot control in the face of opposition to new imperial taxes were accompanied by close to 400 women and 500 children.

Unwilling to live in the barracks on distant Castle Island in Boston Harbor to which resentful Bostonians had relegated them, the soldiers were forced to rent warehouses, houses and rooms in private homes all over town. About 3,000 Britons and 16,000 townspeople ended up sharing the roughly one-square-mile peninsula that comprised pre-revolutionary Boston. Not surprisingly, civilians and soldiers intermingled and communities connected, albeit uneasily.

Of course, there were tensions. As military custom required, soldiers challenged people walking by guard posts. Politicized Bostonians considered this an assault on their liberty. Their refusals to answer challenged army authority and created friction. Moreover, there were drunken brawls, curses, “indelicate threatenings” and regular violent clashes on city streets, some involving women.

But the landlords and tenants also exchanged coal and the proverbial neighborly cups of sugar, visited and worked together, and attended the same churches. To the horror of local patriots, soldiers and female Bostonians flirted and romanced. Some wed. One in four nuptials in Boston between 1768 and 1772 involved British soldiers and local women. Zabin’s in-depth research allows her to track a number of these couples. Although some Bostonians rejected these unions as a betrayal of the American cause, others publicly embraced the new “imperial” families. New Englanders also eagerly aided soldiers keen to escape from the army. Unusually large numbers of deserters absconded into the surrounding countryside, where they, too, became neighbors, friends, husbands and fathers.

Trending

As time wore on, relations between civilians and soldiers became progressively volatile. Zabin points out that such unpredictability was not peculiar to Boston. Explosive civilian-military relations were common, given the use of soldiers for crowd control in peace time throughout the British Empire. Increasingly resentful of military occupation, Bostonians were exquisitely sensitive to any slight or innocent misstep. “Every morning,” Zabin writes, “was a roll of the dice: Would this be another day of favors exchanged and drinks shared? Or would this be a day when a comment became a shove or a brawl became a riot?”

As to the actual events on the evening of March 5, 1770, we are still in the dark, despite the accounts of several hundred witnesses who said they had seen or heard something important. Their stories diverged widely, and the number of actual observers was in question. Were just a few dozen people in the immediate area or hundreds? Did restrained redcoats fire in self-defense as townspeople armed with clubs pelted them with sticks, ice and snow, or did they shoot willfully on well-behaving and unarmed folk? Did Capt. Thomas Preston order his men to fire or did he try to hold them back? Had it all been an unfortunate accident?

Although the fascinating testimonies Zabin details do not agree on how events unfolded, they do show that people encountered one another that evening as community members, rather than as faceless civilians and soldiers. It was the trials at the end of 1770, first of Preston and then of eight of his soldiers, she argues convincingly, that turned the familiar redcoats into anonymous strangers. For different reasons, lawyers on both sides erased any neighborly and familial ties and created a narrative of two separate and opposing camps of civilians and soldiers.

This “political spin,” Zabin points out, also contributed to the “disappearance” of the families and “all women, both civilian and military, associated with this event.” Their absence in the historical narrative extends well beyond the Boston Massacre and remains an issue for historians wanting to point out the centrality of family and gender in understanding the revolution and the War of Independence.

In the epilogue of her engaging book, Zabin observes that the Boston Massacre was a family brawl that broke down the familial relations between the mother country and her colonial children, just as the revolutionary conflict split actual families and friendships on both sides of the ocean. “We think of the American Revolution as a political event,” she concludes, “but it was much more like a bad divorce.”

– Reviewed by Marjoleine Kars, who is a historian at the University of Maryland at Baltimore County. Her book “Blood on the River: A Chronicle of Mutiny and Freedom on the Wild Coast,” about the 1763-1764 Berbice slave rebellion, will be published in August.