Book review: ‘The Bomb’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, April 17, 2022

- BOOK REVIEW

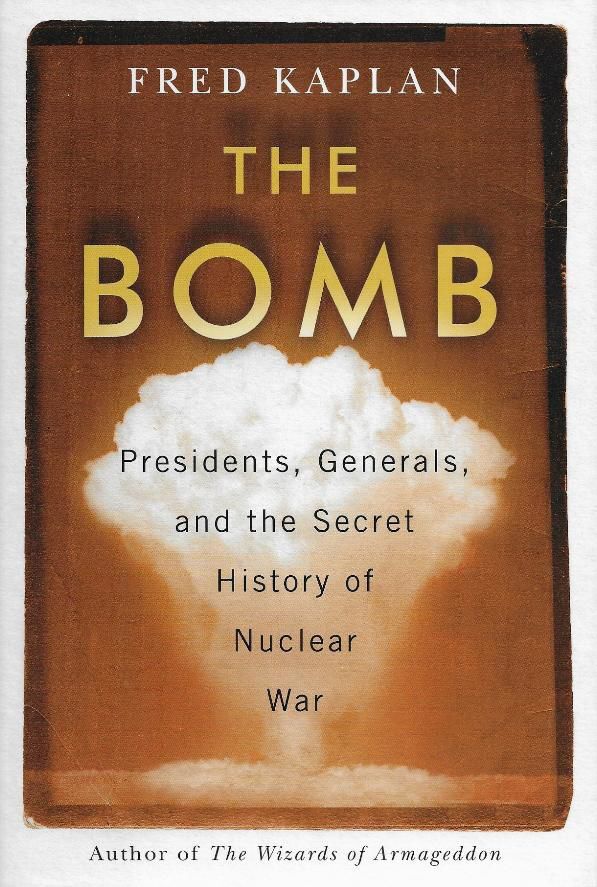

“The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War” by Fred Kaplan. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2020. 384 pages, $30 (hardcover).

“At first, President Harry Truman resisted this juggernaut,” Fred Kaplan notes in “The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War,” his recent attempt to provide a new perspective on a reality most of us have been living with all of our lives. “Soon after Hiroshima, as he realized the full extent of the new weapon’s devastation, Truman decided not to build any more A-bombs, in case the United Nations banned them. When it became clear that this wasn’t going to happen and that the Russians were getting aggressive in Berlin, he cranked up the program.

“But even then, he kept the bomb under civilian control,” Kaplan continues. “For several years, the Air Force had to go through the Atomic Energy Commission even to load the weapons onto their planes. Much of the history of the bomb over the subsequent 70 years, and doubtless beyond, is the story of the generals – and many civilian strategists, as well – trying to make it a ‘military weapon’ after all. Besides, the bomb was, by and large, popular. Tensions between the United States and its largest wartime ally, the Soviet Union, had been brewing since their joint victory.”

So begins Kaplan’s dissection and re-imagining of the role nuclear weapons have played on the world stage for the past 70 years or so. Admittedly, I have had an interest in the topic for most of my life – going back to my high school days when I first became acutely aware of the tenuous nature of our existence on this planet. The splitting of the atom has been both a blessing and a curse; certainly, it has precipitated new options for resolving conflicts that inherently entail both advantages and disadvantages. Nuclear weapons have no doubt prevented numerous international disputes from escalating into full-scale hostilities. But they have also been the impetus for competing military and geopolitical philosophies and strategies that continue to shape both domestic as well as foreign policy.

“The Bomb” is extensively researched, with 44 pages of source notes at the conclusion of the introduction and 11 chapters that form the main text. I was especially appreciative of the eight-page gallery of historical pictures that serve to bring the narrative to life in a way that would not have been possible without its inclusion. Kaplan provides an in-depth and detailed chronology of the development and subsequent impact nuclear weapons have had on the geopolitical landscape of our country since their initial introduction in the 1940s. Those unfamiliar with the saga will find it fascinating as well as unsettling; readers with a rudimentary knowledge of the subject matter will no doubt find some new insights – and discover new complexities that are inherent in a world that is always about a half-hour away from total annihilation.

The author approaches the evolution of nuclear weapons – and the policies and protocols that inevitably accompany that progression – with an overtly critical eye that reveals how things often happen in the proverbial real world. As it turns out, the comprehensive oversight and integration necessary to keep the world from ending suddenly is not as bullet-proof as many of us would like to believe. Silos are treacherous to any organization; they can be particularly deadly when they occur within the structures designed to prevent mass destruction from raining down on humanity as the result of a miscalculation on the part of an increasing number of parties.

“The pivotal moment in the arms race arrived – the ceaseless, 40-year buildup of the U.S. nuclear arsenal took a turn, then drew down sharply – when a civil servant named Franklin Miller took a close look at the SIOP (Single Integrated Operational Plan),” Kaplan explains in “Pulling Back the Curtain,” the eighth chapter and one I found intensely instructive. “Owing to a bureaucratic quirk, Miller’s job gave him a role in coordinating policy on nuclear doctrine and arms control, but not on nuclear targeting – not on how many weapons the Strategic Air Command should have or how it could use them in a nuclear war.”

“Miller detected a serious anomaly,” the author observes. “When he took the job, he read all of the Top Secret nuclear guidance documents signed not only by Caspar Weinberger, the current secretary of defense, but also by his predecessors under all the presidents dating back to John F. Kennedy. Miller knew about the Limited Nuclear Options and Selective Attack Options, the order to hold back a reserve force in the early phase of a war, the policies of controlling escalation and limiting damage in case deterrence failed. And yet, when he sat in on the annual SIOP briefing, which the SAC commander delivered at the Pentagon, he heard nothing about these options or policies.”

Obviously right hand/left hand discrepancies can arise in any organization; in very few situations, however, could they have the potential consequences intrinsic to keeping our nuclear capabilities in check.

Kaplan, the national security columnist for Slate, has written for a number of publications, including The New York Times, The Washington Post, The New Yorker, The Atlantic and Foreign Affairs. A Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and New America, he graduated from Oberlin College and has a Ph.D. from M.I.T. His previous books include “Dark Territory: The Secret History of Cyber War,” “The Insurgent: David Petraeus and the Plot to Change the American Way of War” and “The Wizards of Armageddon.”

In a recent interview, Kaplan was asked what surprised him the most when he was doing the research for the book. His response was enlightening: “I hadn’t realized just how excessive the U.S. nuclear arsenal was. As recently as 1990, around the end of the Cold War, the official war plan called for firing 689 nuclear weapons at Moscow. We also aimed 725 nukes at the Soviet transportation network, 17 nukes at a bomber base in the Arctic Circle that couldn’t be used for most of the year. It was insane.”

Yes it was. And is. “The Bomb” takes us right up to the current moment in history; in fact, Kaplan devotes an entire chapter to the policies espoused by the Trump administration. I came away from that one both scared and reassured. There are mechanisms in place designed to make sure we do not destroy ourselves on a whim. Highly recommended – but not for the faint of heart.

– Reviewed by Aaron W. Hughey, University Distinguished Professor, Department of Counseling and Student Affairs, Western Kentucky University.