Book review: ‘Across the River’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 22, 2021

- BOOK REVIEW

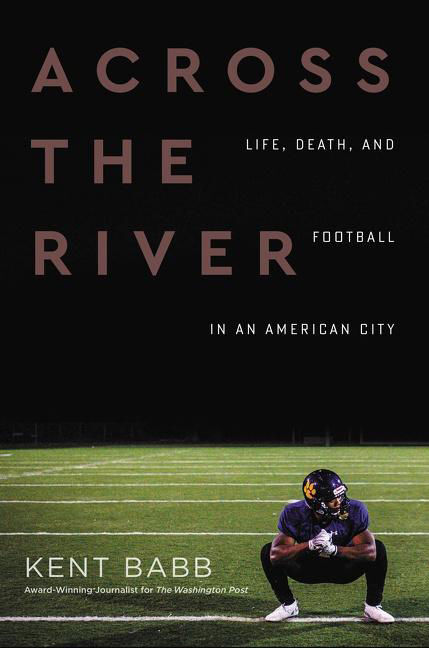

“Across the River: Life, Death, and Football in an American City” by Kent Babb. HarperOne. 336 pp. $27.99. Review provided by The Washington Post.

Brice Brown is head football coach at Edna Karr High School in Algiers, a turbulent and terrifying section of New Orleans, across the Mississippi River from the French Quarter and the Superdome. On a Friday night in June 2016 he received a phone call. Tonka George, once his star quarterback and a recent graduate of Alcorn State University, had been killed in a drive-by shooting.

The coach hauled his 400-pound frame into his battered old truck and drove toward a nightmare of garish police lights and yellow crime tape. “Brown just stood there, staring emptily into chaos,” Kent Babb writes in “Across the River: Life, Death, and Football in an American City.” “Tonka had been a model citizen, had inspired the neighborhood, and … even he got killed. It was a stark reminder that, around here, no one is safe. Brown couldn’t yet know how much this experience would change him, his coaching philosophy, the Karr football program. He was only certain of one thing: standing at a crime scene, he never wanted to feel this ever again.”

This grim and gripping narrative follows Brown and the Karr team through the 2019 season as the coach grapples with the fallout from Tonka’s death and struggles to protect his players from the violence that surrounds them. “Just as a quarterback learns to recognize and beat a blitz, young men in New Orleans must learn to identify a possible crisis – and know how to de-escalate it,” the author writes. “Around here, that can be a matter of life and death.”

Babb is a sportswriter for The Washington Post, and this book grew out of an article he published in 2018. Karr’s team is all Black, and Babb is a southern White man, yet he gains the trust of the key characters and bears witness to the texture and truth of their lives. “I want to show you this world, and I want you to see it as I did: unfiltered and unpolished,” he writes.

Language is central to that goal. The book is heavily laced with obscenities, which are quoted in full, but the players and coaches also use the n-word frequently – not as an insult but as a badge of identity and solidarity. Babb describes a player calling a team meeting to order: “ ‘Where my n—-s at?!’ he yells, punching the air. ‘Uh-UHHHH!’ his teammates shout back.” The author and his publishers discussed the issue at length and agreed on a compromise: They would not “censor” the language he heard, but they would not spell out the n-word either, “the most divisive and incendiary word in the English language.” I agree with their solution. One strength of this book is its “unfiltered” treatment of highly charged racial themes, and candor is critical.

Karr’s coaches worry, for instance, that the team’s complexion can be a source of weakness as well as strength. After a dozen years on the staff, assistant Norm Randall “has developed a theory,” Babb writes: “In general, players here are aggressive, confident and fearless – until they play an opponent from a predominantly White school. In those games they lose their tempers. They abandon their training and make mistakes. Norm believes they play as if they don’t deserve to win.” This conviction leads the coaches to a larger goal. They have to shape mind-sets as well as muscles. They’re not dealing just with X’s and O’s but also with IDs and egos. “Self-worth is both the most difficult and most essential thing Brown and his assistants try to instill in this yearly assemblage of damaged souls,” Babb writes.

Nurturing spiritual strength helps win games. More important, it helps prepare Karr’s players for life after high school and after football. In fact, Brown believes, building character can be more vital than scoring touchdowns. During the state championship game, a sophomore wide receiver named Aaron Anderson kept dropping passes, and the coach felt pressure to bench the youngster, but Brown refused. “This is a football game, yes,” Babb writes. “But Aaron is a kid. Whatever happens next could stick with him forever. Brown opts to send Aaron back in. It’s a massive risk, and even the assistant coaches are skeptical of this. Brown, though, cares about Aaron and wants to show he believes in him.”

I won’t reveal how the game ends, but that’s not really the point anyway, because this engrossing book is not really about football. It’s about how caring, committed adults can make a huge difference in the lives of young people, especially Black males who are threatened every day with psychological and physical turmoil. Ronnie Jackson, a premier running back at Karr who got a scholarship to the University of Texas at San Antonio and then left during his freshman year, tells Babb that even some of his relatives were secretly pleased when he washed out, because his previous success had highlighted their failure. “New Orleans is like crabs in a bucket,” he said. “Every time that crab about to go out, something just pull it back in; ‘If I can’t leave, you can’t leave.’ ”

Brown’s mission, and message, is pretty simple. By believing in his players, he hopes to help them climb out of the bucket. He did that himself. After growing up in Algiers and living through his father’s murder, he played football at Grambling State, about 300 miles northwest of New Orleans. But then he climbed back in, to take the job at Karr, and he keeps turning down offers to leave. He endures so others can escape. He suffers so others can survive. And as he drives to every game, he plays his favorite gospel song, “I’m Not Tired Yet,” sung by the Mississippi Mass Choir. “Noooo! I’m not tired yet!” goes the refrain. “No, no, no!”

– Reviewed by Steven V. Roberts, who teaches journalism and politics at George Washington University.