Book review: ‘A Synthesizing Mind’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, February 28, 2021

- BOOK REVIEW

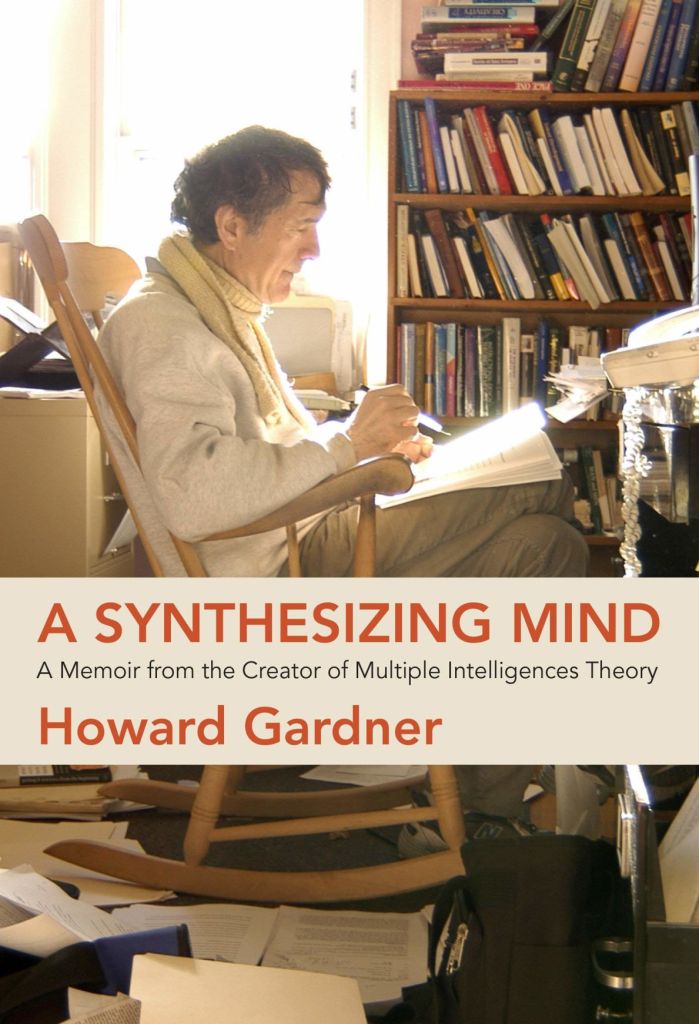

“A Synthesizing Mind: A Memoir from the Creator of Multiple Intelligences Theory” by Howard Gardner. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2020. 304 pages, $29.95 (hardcover).

“Growing up in Germany, my parents were typical comfortable young people of the 1920s,” Howard Gardner explains near the beginning of “A Synthesizing Mind: A Memoir from the Creator of Multiple Intelligences Theory,” his account of the events that precipitated his groundbreaking theory. “They danced, partied, skied and were quite social. But having lost a child in a sledding accident, they were very protective of me. They did not want me to be involved in any activity that might result in serious injury.

Trending

“I was essentially barred from any sports, never skied, never played tackle football,” he continues. “I did not ride a bicycle until I was in my 20s, long out of the family home, and have never felt fully comfortable on two wheels. I was not antisocial but, as seen in the opening cameo, my major activities were solitary – reading widely, writing regularly and playing the piano assiduously. Even today, I prefer swimming to any team sports. I always had a few close friends and was reasonably social with those I knew well. But I was hardly gregarious, let alone the life of the party.”

So begins a thoroughly engrossing dissection of the interplay between the personal life of one of our most distinguished cognitive psychologists and the revolutionary idea that still resonates with educators and practitioners across a number of disciplines. I was familiar with his theory, but I did not know Gardner’s family escaped Nazi Germany by moving to the United States in 1938 (the same year my parents were born), that his older brother was killed in a tragic sledding accident six months before he was born and how those experiences ultimately shaped the person he eventually became and the genesis of the profound influence he has had over the years.

“Many years later,” Gardner notes. “my parents told me that had my mother not been three months pregnant with me, they would have killed themselves. From their point of view, they had lost everything – their home country, their occupations, many friends and members of their extended families, and now what was most precious to them, a very gifted young child.”

Full disclosure: I bought his seminal work, “Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences,” when it was first published in 1983, and I have been fascinated by Gardner’s philosophical framework for most of my career. His ideas have been discussed extensively in several of my graduate courses over the years, most prominently in “Testing and Assessment,” which delves extensively into what constitutes “intelligence.” I have always agreed with his central thesis that intelligence is not a single characteristic concerned primarily with the cognitive domain. But until I had the opportunity to actually see inside his mind, I really only understood his ideas on a one-dimensional, intellectual level. This book gives us, as Paul Harvey used to say, the rest of the story. Turns out, the creator is at least as interesting as his creation.

The book is comprised of an introduction followed by 12 chapters arranged in three sections: “Part I: The Formation of a Synthesizing Mind,” “Part II: Multiple Intelligences: Reframing a Human Conversation” and “Part III: Unpacking the Synthesizing Mind.” I was especially intrigued by the inclusion of an appendix listing Gardner’s blog posts from 2012 through 2019, which provides a chronological description of how his thinking evolved over the last eight years.

Part biography, part confession and part attempt to fill in the gaps so that the record is more complete, I believe “A Synthesizing Mind” succeeds at accomplishing everything Gardner set out to do when he decided to write this succinct yet amazingly astute primer on his life, times and thinking. Even if you are intimately familiar with his ideas – and the countless critiques from both his disciples as well as his detractors – you should not assume that you know who Gardner is and what drives him to continue working a breakneck pace even as he approaches 80. Although the entire book is essentially autobiographical, I was particularly drawn to “My Scattered Pursuits and the Mind that Connects Them,” the 11th chapter and one I found to be especially instructive:

Trending

“For whatever reason, I have always been curious. I become interested in things I hear about, read about or observe as I make my way around the world. I investigate them with whatever means are available. And I like to write about them, both to make sense to myself – how do I know what I think until I have seen what I have written? – and to convey my thoughts to others who may share my curiosity. Why else did I produce a newspaper as early as second grade? Why did I aspire to edit the ‘Opinator,’ that weekly high school publication? And why do I continue to post these blogs every other week, till this day? (Between 2015 and the end of 2019, I have published nearly three hundred blog posts.)”

The author of 30 previous books, Gardner is the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Research Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, as well as senior director of Harvard Project Zero, a research center founded in 1967 that explores topics such as deep thinking, understanding, intelligence, creativity and ethics. Twice selected by Foreign Policy and Prospect magazines as one of 100 most influential public intellectuals in the world, he is the recipient of several prestigious awards, including a MacArthur Prize Fellowship and a Fellowship from the John S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. Moreover, Gardner was also the first American to receive the University of Louisville’s Grawemeyer Award in Education. His books have been translated into 32 languages; he is primarily known for his theory of multiple intelligences.

Perhaps the best advice I received personally from “A Synthesizing Mind” came from the admonitions Gardner gave in “Understanding the Synthesizing Mind,” the concluding chapter: “Should you have the privilege of changing the conversation, be grateful. Don’t assume that you can control the ensuing conversation – you will in all likelihood fail – but you do have a responsibility to help guide it in productive ways.”

I could not agree more. Highly recommended.

– Reviewed by Aaron W. Hughey, University Distinguished Professor, Department of Counseling and Student Affairs, Western Kentucky University.