Book review: ‘A Good American Family’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 9, 2019

- BOOK REVIEW

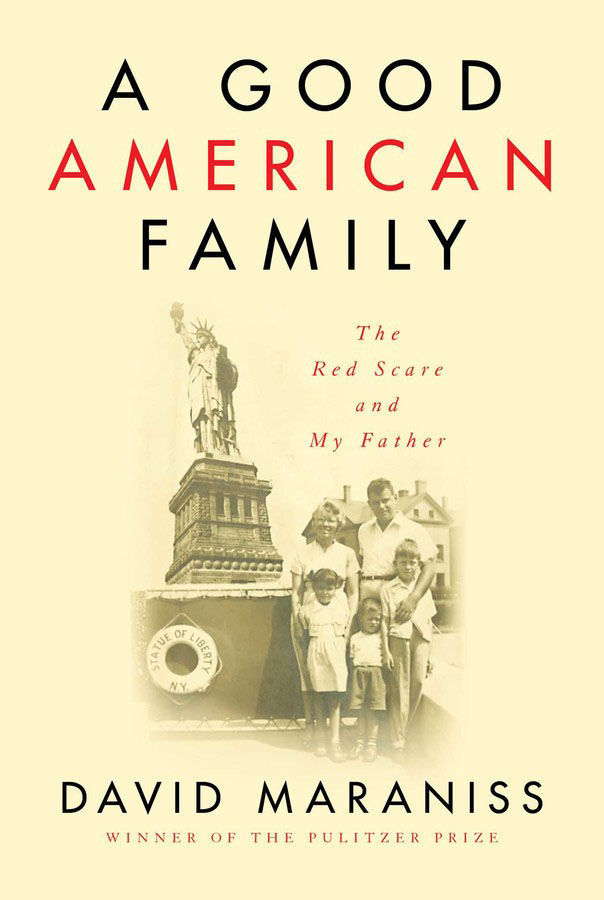

“A Good American Family: The Red Scare and My Father” by David Maraniss. Simon & Schuster. 416 pp. $28. Review provided by The Washington Post.

Once it was over, Elliott Maraniss did not talk much about his life as a communist. As far as his son David knew while growing up, Elliott was just an all-American dad, a father of four and editor of a Wisconsin newspaper. For a decade and a half, though, from college up until David was almost 3, Elliott devoted much of that energy and passion to work within the communist orbit, throwing himself into fights for labor rights, racial justice and anti-fascism while looking for guidance to the Soviet Union. In 1952, at the height of McCarthyism, he was called in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee to answer for his commitments.

“A Good American Family” is his son’s moving attempt to recover what happened during those years. A veteran Washington Post journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner, David Maraniss is not out to expose his father’s secrets. To the contrary, he adores the man who raised him. “It is hard for me to overstate how much of a force for good he was not only in my life and those of my siblings, but also in the lives of scores of newspaper people, professional acquaintances and friends of the family,” David writes. “But there was a time when Elliott Maraniss was a communist.”

The son sees in this a contradiction worth exploring: How could his father have been a loving parent and a patriotic citizen and at the same time have flirted with Stalinism?

From a biographical perspective, there may be less to explain than this framing might suggest. Born in Boston in 1918, Elliott grew up mostly in the milieu of Jewish Brooklyn, where political radicalism was simply in the air. Elliott’s father had been a “Wobbly,” a member of the militant Industrial Workers of the World. His high school principal was a socialist, devoted to educating the younger generation in the fine arts of skepticism and economic justice. Among the impressionable students at Elliott’s high school was the future playwright Arthur Miller, who would go on to write searing critiques of American capitalism and its spiritual cruelties, including “Death of a Salesman” and “The Crucible.” In such an environment, Elliott’s choice to become a communist was less a dramatic break than one available option.

In the mid-1930s, Elliott carried this ethos to the University of Michigan, where he quickly found a home within the passionate student left. While there, he also encountered powerful examples of radicalism in action. In one of the most engaging chapters of the book, David describes the heroic if illegal overseas journey of three young University of Michigan graduates, determined to fight in the Spanish Civil War as part of the communist-led Abraham Lincoln Brigade. Only two of those students returned alive, but when they did, some 600 Michigan students turned out for a banquet to celebrate them – “and that is how my parents met,” David writes. At that point, his mother, Mary – just 17 years old – was already a communist herself. Her brother was one of the boys returning from battle.

If this brand of radical politics was not so unusual in the 1930s, what distinguished Elliott and Mary is that they stayed on long after others left. For many young radicals of the era, the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939 marked a moment of disillusionment, an about-face by Stalin after years of outspoken opposition to fascism. Not so for Elliott and Mary. To the contrary, they followed the Soviet line and remained committed to communism, even as they got married and started a family. Their political practice led them not into espionage or subterfuge, but into causes that many Americans would now champion. During the war, Elliott served as an officer for an all-black segregated Army unit, a post rejected by many white officers but often sought out by communists committed to racial justice. Mary worked in defense plants while acting as a union steward in the UAW, one of the great industrial unions that communist organizers helped create. When the war ended, they resumed their work together in the Young Communist League, the Progressive Party and the Civil Rights Congress, all while immersed in the thoroughly American baby boom project of expanding their nuclear family.

David speculates that his father might have abandoned communism after the war if his mother, the more somber and doctrinaire of the two, hadn’t pushed him to stay. The case is circumstantial: Elliott was so expansive and loving, with so much sympathy for human contradiction, that the idea of him as a lock-step Stalinist does not compute for his son. The book provides ample evidence of Elliott’s fine qualities, including a remarkably tender wartime letter written to his newborn son, Jim. But the conceit itself – that these qualities would somehow make him less of a communist – does not quite hold up. It seems far more likely that Elliott was not a grand exception: that, in contrast to our popular image of communists as ideological automatons or vicious spies, their world was full of big-hearted, passionate, intelligent people like Elliott and Mary, searching for a way to make a difference.

For the Maraniss parents, the whole project came crashing down in 1952, when the HUAC decided to hold hearings in Detroit. On the day he received his subpoena to testify, Elliott was fired from his copy-reading job at the Hearst-owned Detroit Times. (For reasons not specified, Mary was not called before the committee.) The family then spent several years bouncing around in search of work for Elliott, their movements regularly tracked by the FBI. It was during this period that the parents finally broke from communism. After several years of difficulty, the family finally settled in Madison, Wis., where Elliott built a successful career as a local editor and newsman, and set about rewriting his life.

By Hollywood standards, this is not an especially dramatic Red Scare story. But this more subdued story tells us something equally important about how the Red Scare worked. Elliott’s persecutors came from the FBI and the HUAC, institutions that long outlasted McCarthy. And like most people targeted by the federal government, Elliott was not, exactly, wrongly accused. David argues persuasively that his father’s long-standing communist affiliation did not justify his firing and public humiliation.

– Reviewed by Beverly Gage, a professor of history at Yale who is writing a biography of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover.