Bingham delivers a legacy in letters

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 1, 2015

- Sallie Bingham’s latest memoir, “The Blue Box: Three Lives in Letters,” deftly unfolds the tucked-away and untold stories, a letter at a time, of three generations (1850-1960s) of women – her great-grandmother Sallie (her namesake); her grandmother Helena; and her mother, Mary – in an historical literary journey, the findings of which not only “disturb ... the official record” but often set it straight.

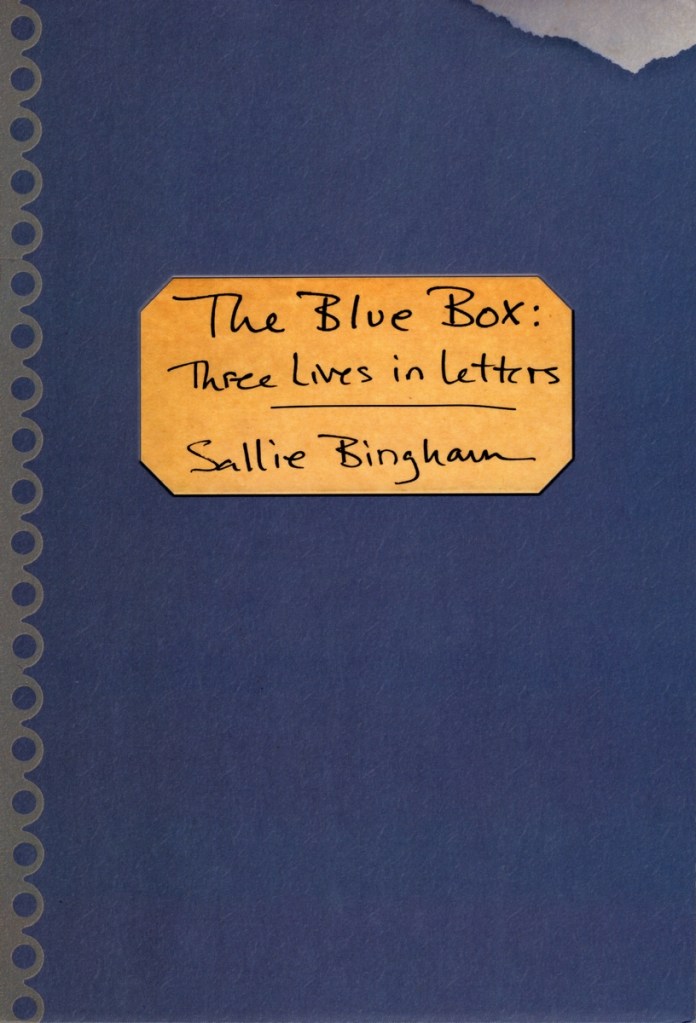

“The Blue Box: Three Lives in Letters,” by Sallie Bingham. Louisville: Sarabande Books, 2014. 230 pages, $15.95. ISBN: 978-1-936747-78-8.

Sallie Bingham’s latest memoir, “The Blue Box: Three Lives in Letters,” deftly unfolds the tucked-away and untold stories, a letter at a time, of three generations (1850-1960s) of women – her great-grandmother Sallie (her namesake); her grandmother Helena; and her mother, Mary – in an historical literary journey, the findings of which not only “disturb … the official record” but often set it straight.

Trending

After their mother’s death, Bingham’s sister Eleanor discovered “a large, cornflower blue box on the top shelf of Mary’s closet.” The box contained more than a century’s worth of letters, books, photographs, keepsakes and official documents of not one but three women. Already a prolific and accomplished writer, Bingham was naturally the daughter chosen to receive these articles otherwise bound for the trash. And from this “nest” of papers and documents, Bingham set about the painstaking task of organizing and then distilling the stories of these seemingly very public, yet intensely private, lives. Much of what was known about the family previously had been passed down orally. The box’s contents grew into packets and carefully organized layers. Yet the real task lay in Sallie Bingham’s hands: re-creating three lives from vintage documents.

As Bingham discovered, all three of these Southern women were prolific writers, though their audience was limited, given propriety’s patriarchal restrictions. Only Helena published for profit, and even her fiction pieces were constrained, suited to the readership of the day. It is evident these women were connoisseurs of finer things and enjoyed vast libraries and education; their intelligence, refinement and politesse were manifest in their writings – much of which emanated from their complete emulsion in the caste system – along with belief in a hierarchical system of which they represented the crest.

Bingham’s great-grandmother Sallie Montague enjoyed life as a debutante of the antebellum South, along with all the lavish ends whose means meant slavery. Her education expounded on developing and nurturing language and other distinguishing characteristics that encouraged blissful (and sometimes willful) ignorance of the race, class and social divides created for their benefit. The result of her immersion in education (specifically the classics) was an exquisite command of language and understanding that belied gendered notions of women’s capabilities of the time. Her marriage to Arthur Lefroy from Ireland expanded her status, socially and economically. His equally well-heeled family was a “cultivated landed gentry that was happily supported, economically and physically, by an idealized peasantry.”

While tiny and seemingly delicate, the antebellum Sallie was fierce in her determination to continue the legacy entrusted her and to maintain dignity in the face of adversity – especially after the loss of her young, prosperous husband to tuberculosis. Bingham says of Sallie’s essays, “Each a lecture she presented, (were) tied up with a half hitch, a reminder of the knots she learned as a horsewoman. When I untied the delicate cord, I realized the knot had held for more than a hundred years … Yet these folded papers mark, for me, the beginning of the era that might free my grandmother and my mother from many of the constraints – an inability to admit pain, for instance, a constant conflation of worth, race and economic class.”

Known as the First Family of Virginia, Bingham’s grandmothers and mother found themselves representatives of an aristocracy – even in times of family misfortune – while “cocooned” in a “social system” that demanded they maintain the air and appearance of an ostentatious lifestyle even while, as in her grandmother Helena’s life, experiencing extreme financial difficulties. Even when reduced to near-poverty (as happened with all three women – at least briefly), fine manners and language distinguished and exalted their class. Outsiders, for all appearances’ sake, were vaguely, if at all, aware of their circumstances. This was necessary. Language, in essence “beautiful language,” effectively divided the learned from the lesser classes. To survive and maintain her dignity, Helena was culturally bound to this tenet. Bingham says, “This reverence for tradition and the strictures of formality would shape and shackle Helena, as she became the family’s first professional writer.” Bingham also writes, “Helena defended, throughout her life, the tenets of the South’s belief in an inherent aristocratic and racial supremacy, and these beliefs hobbled her writing.” While her short stories were embraced in her own social circle, they have not endured the vicissitudes of class definitions and modern civility. Thus, the voice of a talented writer has all but been silenced.

Sandwiched between the author and the first Sallie was Mary – Helena’s daughter and Bingham’s mother – a woman who was burdened by the mores of the previous generation and the desires of a generation that bobbed their hair, shortened their skirts and tried to reconcile the two. Most importantly, she embraced education with a fervor reserved mostly for men. She was awarded both a scholarship and a much coveted fellowship that, due to the extreme parietal environment women had to endure, she ultimately had to defend or lose. The elusiveness and secret life of Barry Bingham, her future husband, presented an even greater challenge for her.

Trending

“The Blue Box” is more than a memoir; it’s an historical account of the legacies, heritages and travails of three generations of Southern women. Contemporary readers may be unable to identify with the attitudes and mores of the women in Bingham’s book (and may, at times, find those beliefs uncomfortable), but in the women’s minds, they were obeying a long-standing system that had been effective for centuries. While the “system” was all they knew, they attempted rebellion through the written word. They were resilient, strong and keenly protective of their families, yet they took liberties prohibited for their class at that time – writing essays and opinions outside the norm. Bingham has woven these words into an accurate portrayal of historical events that encumbered many women of this time and presented them to us in the living language of complex and exquisitely-preserved letters. Sallie Bingham’s meticulous and comprehensive work gives us a glimpse into another world – previously frozen in a “cornflower blue” time capsule.

— Reviewed by Trish Lindsey Jaggers, assistant professor of English, School of University Studies, University College, Western Kentucky University

— Editor’s note: The 19th annual Jim Wayne Miller Celebration of Writing will be at 2 p.m. Nov. 8 in the Kentucky Room of the Kentucky Library and Museum. Sallie Bingham will present a reading from her latest memoir. A book signing and reception will follow the reading. It’s free and open to the public.