Farmer says business killing livestock

Published 12:00 am Saturday, April 8, 2006

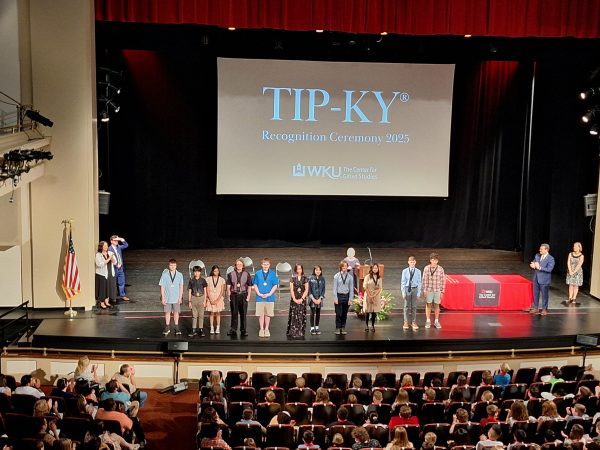

- Photos by Joe Imel/Daily News Page Barker stands Thursday in a ditch that he says carries contaminated water onto his family farm across the street from the Schochoh Farm Center on Ky. 663 in Logan County.

After enduring years of allegedly contaminated water streaming onto the family farm, an Adairville man is suing the agribusiness across the street he said is responsible for poisoning several of his animals.

Page Barker, 41, said the water, which contains elevated levels of nitrogen and other chemicals, seeps onto the farm through two ditches under Schochoh Road from the Schochoh Farm Center, an agricultural supply facility owned by Royster-Clark Inc. Royster-Clark denies any wrongdoing.

“Royster-Clark is questioning my ability to raise cattle,” Barker said. “I’ve raised cattle since I was 13 – I know cattle.”

The runoff has contaminated the family’s pond and a well, he said, causing him to pay $150 a month for city water. The farm is the only one in the family saddled with sick cows and goats, where he estimates losses in the thousands.

“This ought to be our best herd, but it’s the worst,” Barker said.

The family owns 400 acres, rents 1,600 acres, and has farmed since 1963.

“We’ve been here a lot longer than Royster-Clark has,” Barker said.

Staving off the runoff is important, he said, because his 15-year-old son, Lee, wants to follow in his farming footsteps.

Barker is also concerned about his family’s health after being exposed to the water for so long. He said his older daughter constantly had kidney infections growing up.

His animals started getting sick and dying off in the 1980s, but he said he could never prove the cause. Though not admissible in court, a logbook Barker keeps purports 45 calves, 27 cows and 11 goats have died since 1980.

“It costs a lot of money to fight a big company,” he said.

Royster-Clark, based in Norfolk, Va., is the largest U.S. fertilizer retailer, with locations in 23 states, according to company statistics.

Mark Alcott, the company’s attorney, denied Barker’s allegations. He said he didn’t want to “give credence to Mr. Barker’s story.”

In an answer to a lawsuit filed by Barker in U.S. District Court in Bowling Green, Royster-Clark admits owning the Schochoh Farm Center, but denies ownership of the property it sits on.

The company acknowledged it received “a notice of violation regarding stormwater discharges at our Adairville, Ky., facility” and asked for time to develop stormwater controls, according to a letter to the Kentucky Department for Environmental Protection.

Kentucky Division of Water spokesperson Maleva Chamberlain said the facility’s ditches on the southeast and south sides have no vegetation to filter and slow runoff.

The Kentucky Division of Waste Management collected water samples at the ditches in December. Elevated levels of ammonia, nitrate-nitrite, phosphorous and potassium were found. Elevated pesticide levels were also documented.

As a result, the cabinet recommended the company develop a strategy to prevent the chemicals from leaving its property.

“At this point in time, it is only a recommendation. I expect that they will contact us,” said Bill Burger, manager of the cabinet’s field operations branch in Frankfort. “They might have a counterproposal in addressing (the situation).”

The only change since his complaints, Barker said, is the company sucks liquid nitrogen tanks with a pump and transports the waste somewhere else, as opposed to pumping it into the ditches like before.

But the company still doesn’t sweep fertilizer or secure chemicals adequately, he said.

“They opened the ditch up more just to tick me off,” Barker said.

The company doesn’t want to admit guilt because that would open the floodgates for litigation, he said.

However, a former facility manager, Bob Allen, said he sprayed Barker’s land – a more than $1,000 value – in 1988 to settle livestock losses off the books, although company superiors probably weren’t aware of the arrangement.

“It was more of a mutual friend-customer relations way of handling it. Was that the right way to handle it, 20 years later?” Allen asked. “Maybe not, but it seemed like it worked at the time.”

Barker’s attorney, Wanda Repasky of Louisville, said Royster-Clark was ordered to get a stormwater permit, but no deadline was set.

Repasky said the company has the time and resources to stonewall, so she is proceeding slowly to reduce Barker’s legal costs.

“I took this case because, frankly, I was really insulted at how poorly Mr. Barker was treated by the people across the street,” she said.

In a letter to the company, Repasky wrote: “Rather than addressing Mr. Barker’s concerns, representatives of Royster-Clark have pleaded with Mr. Barker to cease his inquiries regarding the impact of the runoff. … He has received warnings to the effect that he should not notify the Kentucky Division of Water or contact an attorney.”

Barker paid for toxicology and necropsy reports on recent animal deaths from Breathitt Veterinary Center in Hopkinsville, a state laboratory. According to Repasky, the reports indicate the animals died from phosphate poisoning.

“Toxicological analysis indicates the blood levels found in Mr. Barker’s livestock couldn’t be attributed to normal farming practices,” Repasky wrote.

Wade Northington, director of the center, declined to comment on the reports, but said it’s important to find all sources of an animal’s consumption to get a more accurate picture of its death.

“You would try to tie all that together,” he said. “There are some things that are unsolvable.”

Lamenting his losses, Barker cited goats with stinted growth and several stillbirths of calves, as he vowed resiliency.

“They’re trying to wear me out in court,” Barker said. “We’re in it for however long it takes.”