Novel reminiscent of lost Kentucky towns

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 12, 2006

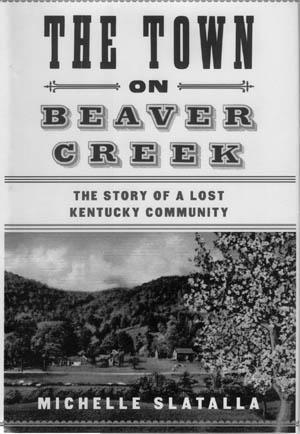

- The Town on Beaver Creek: The Story of a Lost Kentucky Community, by Michelle Slatalla. New York: Random House, 2006. 242 pages, $24.95 (cloth).

Reviewed by James Darrell Skaggs, Department of English, Western Kentucky University

You can take the boy out of the country, the old saying goes, but you can never take the country out of the boy. Michelle Slatalla, neither a boy nor a country girl, somehow manages to convey the truth of this supposedly time-worn adage in her new novel, “The Town on Beaver Creek.” Since my earliest childhood memories recall a similar town that also no longer exists, I was hooked on page one and remained captive to Slatalla’s literary re-creation of “the way we were” 20 chapters and an epilogue later.

“Some things are lost forever,” she laments in the opening chapter; then she revises her pessimistic beginning by adding, later in the same paragraph, “But some things can be found again. What I discovered were memories,” which she lovingly collected and assembled “as truthfully as possible.” Her grandmother, who left Kentucky early in her married-with-family years, “pined away for the hills of Kentucky all the rest of her life.” The stories her grandmother and other family members told form the deep heart’s core of the novel.

Martin in Floyd County is the setting for her intergenerational saga of a family whose history parallels that of many small towns in America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Built on the banks of a river that flooded frequently, Martin never quite learned the lessons nature tried patiently to teach year after year, flood after flood. In fact, many folks (some of whom were Slatalla’s relatives) never believed the day would come when bulldozers would raze the last remnants of this once thriving town that in its heyday claimed a population of just under 1,000 hardy souls.

My “hometown” experience was painfully similar. Kyrock, once the jewel of Edmonson County, no longer exists. But when I walked as a child and spoke like a child (having committed to memory the 13th chapter of First Corinthians), this bustling community of several hundred “hardy souls” formed the commercial and cultural center of the place I still call home. Like Michelle Slatalla, I also meandered here and there across the continent and even wound up in California near where she and her family live today, but I always carried with me the memories of those days before Hiroshima and knowledge of a Holocaust tilted the modern world on its axis and ushered an era we now lovingly label with such meaningless terms as postmodern or contemporary.

In her novel/history/documentary prose masterpiece, Slatalla carefully weaves interviews, newspaper articles, old love letters, court records and any other sources she can beg or borrow from family, friends, acquaintances old and new, and memories of her own childhood spent elsewhere but resplendent with reveries of an era that is truly gone with the modern winds of technology and change. In fact, her father, transplanted to other towns in later times, built a model of Martin in the basement of their home north of the Mason-Dixon line and lovingly added characters, houses, roads, buildings and other replicas of the Martin of his childhood for all to see – and remember.

The characterizations are both unique and universal: a physician who makes moonshine in the hospital basement, a leading citizen who wanders the town’s streets in his bathrobe, a sheriff who wears a bulletproof vest with possible cross-dressing overtones, and various Mynhier (Michelle’s kith and kin) family and friends who are employed by the railroad, the coal mines or other related town and county services essential to the successful running of a community like Martin.

Romances, gunfights, World Wars (of less consequence than the first two items in this series) and the inevitable march of progress leap from the pages of this delightful re-creation of America in its adolescence, a time before the end of innocence, when hope still whispered to families and friends across this “land of the free and home of the brave” – words that inspired even the cynics among us. Slatalla’s metaphor for a lost America resonates with all who long for an authentic glimpse of “Our Town” with echoes of Wolfe’s “Look Homeward, Angel” or Morris’s “North Toward Home.”

I realize, of course, that we can never really return to those lost days of childhood innocence, but I find it amusing that my last two books have the word “home” in the title, and I travel monthly to Edmonson County to visit tombstones and towns and other monuments, small and great, in some sort of Proustian attempt to recall the splendor of the grass of my youth.

A new town is now being built on a not-too-distant hill, and Martin will never again (so THEY say) have to endure the indignity of flood and famine and attendant municipal misfortunes. But author Slatalla and I know that “some things are lost forever.” Her grandparents left in the late ’50s, but she remembers her grandmother pining for the Kentucky hills the rest of her life. The author’s father dismantled his model town when his grandchildren wanted to use the basement for hockey practice. Not a single pew from the Martin Church of Christ remains; likewise, all the bricks from the old high school and the scratchy mohair seats from the Martin Theatre are lost in the new townscape that will feature “a variety of compatible and complementary architectural styles in order to provide visual interest.” There is no mention of a museum or archives in the detailed prospectus for the new community on the hill. Thank the good Lord, as folk here often say, that Ms. Slatalla has preserved precious remnants of the past, her past, our past, for generations yet unborn.