‘Dogland’ though slender, covers a lot of ground

Published 12:36 pm Thursday, August 29, 2024

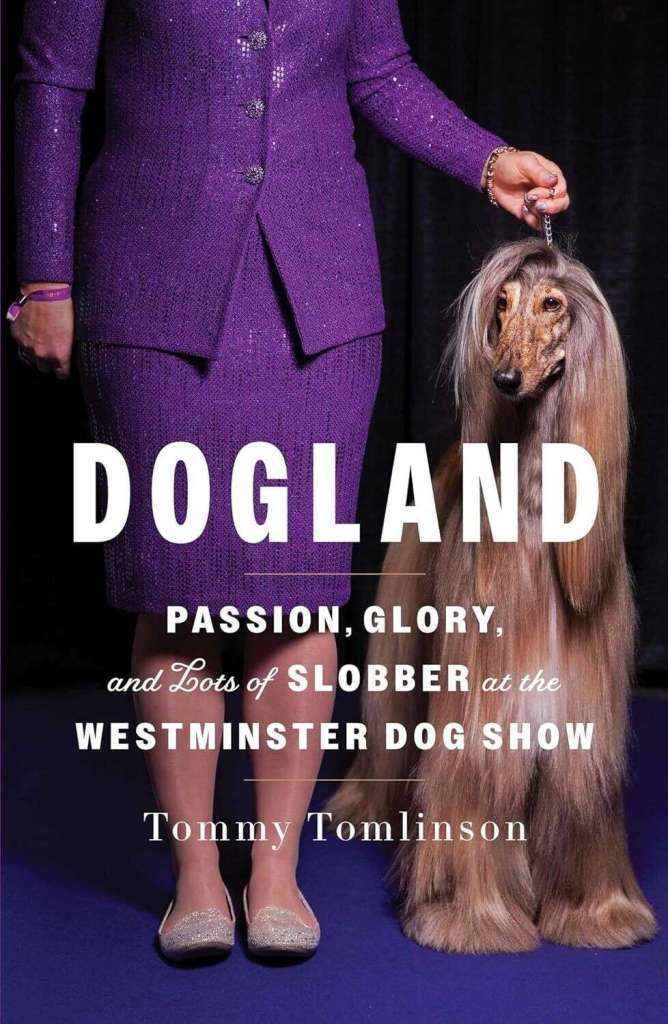

- Cover

“Dogland: Passion, Glory, and lots of Slobber at the Westminster Dog Show,” by Tommy Tomlinson. New York: Avid Reader Press, 2024. 230 pages, $28.99 (hardcover).

For a fun, unpretentious read, “Dogland” covers a lot of ground, taking on doggy evolution, the rise of purebreds, the life and economics of dog handlers, the mechanics and history of the show ring and the dubious standards by which show dogs are judged. Along the way, the author even finds time for jokey sidebars. Example: “Cartoon Dogs Rated,” featuring Goofy, Tramp, Scooby-Doo, and, Snoopy, “decorated pilot, slick-fielding shortstop … and early proponent of River Dance.”

Trending

For all its digressiveness, though, the book has two through-themes, one straight reportage of the dog show campaigning of handler Laura King and Striker, a nearly flawless Samoyed; and one speculative: what have we humans done to dogs and are they happy about it?

Reportage first. Tomlinson attended over a hundred dog shows on the trail of King and Striker (AKA Vanderbilt ’n Printemp’s Lucky Strike), leading up to the 2022 Westminster, where Striker fell a whisker short of being proclaimed best of the best.

Serious dog show people live in an alternate world, he writes. For 50 weeks a year, King shows a stable of dogs from her 42-foot camper. At every stop, she meets other handlers traveling to some of each year’s 1500-plus sanctioned events in RVs stuffed with crated show dogs. Tomlinson compares the scene to “the eternal caravan of Deadheads, except fueled with box wines and Big Macs instead of LSD and falafel.”

A dog has to win points at such local shows to be declared a champion. With enough points, a phenomenon like Striker (200 best in shows) may be invited to the big kahuna – the annual Westminster Show, featuring some three thousand dogs, two hundred breeds and a national TV audience.

At the Westminster as elsewhere, the breeds are divided into seven groups: terriers, toys, working dogs, sporting dogs, hounds, herding dogs, and the nebulously named non-sporting dogs. Entries from each breed compete in preliminary classes for puppies, juniors, older dogs, champions, and so on. The winners then vie for best of breed. Best of breed winners compete for best of group, and the seven group winners go on to the final event, where one will win best in show. Because Samoyeds were developed to pull sleds and guard reindeer, Striker belongs to the Working Group. At Westminster he won his group, but in the final judging lost to Trumpet, a bloodhound.

While that loss disappointed his fans, it didn’t mean Trumpet was the better dog. Show judging goes by written standards for each breed. Striker’s loss simply meant that Trumpet met the bloodhound standard better than Striker did the one for Samoyeds – at least in theory.

Trending

In practice, show judging is more subjective than scientific. The final seven in any big show are all exemplary dogs, and the standards for judging them don’t make for easy comparisons. A Chihuahua’s back should be slightly longer when measured from shoulder to buttocks than its height at the withers. Imagine comparing a winning Chihuahua to a German shepherd, whose back should be longer than its height by a proportion of 8½ to 10, measured, not from shoulder to rear end, but from breastbone to pelvis. No wonder best in show usually depends on how well a particular dog is performing that night.

Tomlinson’s obsession with show dogs seems odd, given his own preference for mutts like Fred, the stray he and his wife coddled for fourteen years. But thinking about Fred got him considering dogs’ age-old relationship with humans. Ever since dogs evolved from wolves, we humans have molded them to suit our own ends, breeding brawny draft dogs, yappy watchdogs, and solicitous shepherds. Along the way, we reshaped them physically, fashioning pencil-thin greyhounds and heavy-coated, web-footed retrievers. We even bred some with big eyes and short snouts, small enough to coddle like the babies they resemble.

Purebred dogs come from a restricted gene pool, and Tomlinson is properly conscious that their inbreeding has led to inherited conditions he catalogs, things like the hip dysplasia that bedevils Great Danes or the breathing and birthing difficulties suffered by bigheaded snorters like our current favorite breed, the French Bulldog.

He worries, too, about stifling dogs’ inherent tendencies. Terriers were bred to dig out pests, shepherds to shepherd, and hunters to hunt. Is it cruel to forbid terriers to dig or to keep beagles indoors when all their instincts tell them to get out and chase rabbits? Striker the Samoyed will never see a reindeer or the Siberian taiga. He’s retired now, but was it cruel to confine him for the first six years of his life to the back of an RV or a show ring? Could he have enjoyed a life so grotesquely different from the one he was bred for?

Happily for dog lovers everywhere, Tomlinson genially answers yes. Dogs thrive when they have a job to do. In a show ring, herding or tracking, or just hanging out, they want to be useful and valued. They’re happy, that is, when they’re making us happy. Thousands of years of directed evolution have made them “happiness spreaders,” able to love whatever work we put them to and, by means of their sympathetic camaraderie, to “find the best in us in ways even other humans often can’t.”

“Dogland” may be a slender book, but it’s one any fan of dogs will learn from and appreciate.

– Reviewed by Joe Glaser, WKU English Department