WKU professor reflects on Vance’s ‘Hillbilly Elegy’

Published 6:00 am Friday, August 9, 2024

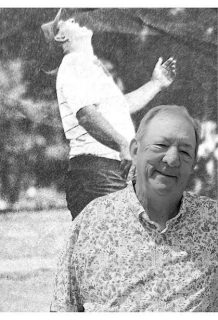

- Western Kentucky University History Professor and American popular culture history scholar Anthony Harkins sits in his office in Cherry Hall on Wednesday morning, Aug. 7, 2024. Author of the 2005 book “Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon,” the 2016 book “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis” and the 2017 anthology “Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy,” Harkins has spent decades directing his body of study toward the history of the representation of the Appalachian region and has been sought nationally for his perspective on the Appalachian ties of Republican vice presidential pick J.D. Vance. (Grace Ramey McDowell/grace.ramey@bgdailynews.com)

For cultural historian Anthony Harkins, becoming a nationally sought perspective on the Appalachian ties of Republican vice presidential pick JD Vance stemmed from a decades-long fascination with one word: “hillbilly.”

“Why is it so long-standing?” said Harkins, a scholar of American popular culture history and a professor at Western Kentucky University. “How does it survive way over a century, when other stereotypes have become unacceptable and intolerable?”

Trending

While he made clear that he is not from Appalachia, Harkins – the author of the 2005 book “Hillbilly: A Cultural History of an American Icon” – has spent decades directing his body of study toward the history of the representation of the region. So, when Vance authored his 2016 book “Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis,” Harkins was asked to co-curate a response, which became the 2019 anthology “Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to Hillbilly Elegy.”

“Hillbilly Elegy” propelled Vance into fame; made Vance the media’s go-to person for Appalachia; and drew the ire of numerous Appalachians who have since penned responses critical that Vance’s memoir set out to define a people instead of a person.

“Appalachia has many stories, many experiences, much diversity, but it generally gets solidified into a single story,” Harkins said. “That was the interest in the book, and our book got a fair amount of interest at the time; and, of course, it’s become relevant again.”

At his vice presidential nomination acceptance speech last month, Vance reaffirmed his ties to Appalachia. News outlets took notice, and the Washington Post contacted Harkins for insight.

“The idea that he should be a voice of an entire 13-state region with differences, that his own story is indicative of a broader society, I find that very problematic,” Harkins told the Washington Post. “He reinforces stereotypes of poverty and frames it as an individual choice instead of larger socioeconomic forces.”

When presidential candidate Donald Trump selected Vance, Harkins realized it would “very much bring (‘Hillbilly Elegy’) back into the national conversation.” Residents and scholars of Appalachia have for years said that while Vance has every right to tell his own story, the book reaffirmed stereotypes as it transitioned from first person to third in an attempt to speak on a collective experience of Appalachia. One instance was when Vance wrote, “Public policy can help, but there is no government that can fix these problems for us … We created them, and only we can fix them.”

Trending

“I think it understates the degree to which larger systems shape people’s lives,” Harkins said of the excerpt. “And that does not discount individual achievement or limitations, but (Vance) says very little about what that public policy would be and a lot about individual choices.”

Harkins added that he has seen Vance, in his political rise, transform his messaging about Appalachia.

“Vance too often frames the people of Appalachia as responsible for bringing their problems on themselves,” Harkins said. “And now that he’s shifted his message to critiquing immigration and foreign competition, he underplays his initial critiques of the so-called culture of Appalachia.”

And, Harkins said, many Appalachian scholars and writers feel that Vance, who spent many summers in Appalachia, overstated his claim to the region, and then used the region and connections to create an exciting story and advance his career – and then disconnect from it.

“These writers worry that this will reinforce a longstanding history of people coming into Appalachia, extracting what they want and then leaving,” Harkins said.