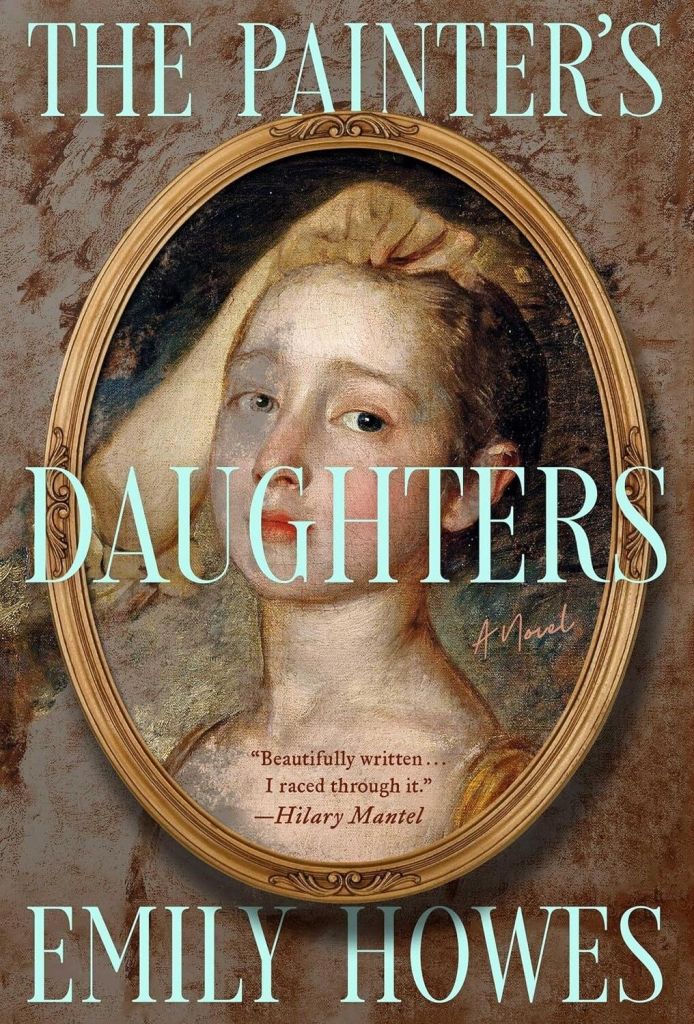

‘The Painter’s Daughters’ a rich, pleasing novel

Published 9:16 am Thursday, March 21, 2024

- Cover

“The Painter’s Daughters: A Novel,” by Emily Howes. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2024. 371 pages, $27.99 (hardcover).

When art history aficionados hear the name Thomas Gainsborough they are likely to recall the image of his Blue Boy or some other portraits or landscapes he painted. If they remember his “The Painter’s Two Daughters,” part of which is illustrated on the book’s cover, or “The Painter’s Daughters Chasing a Butterfly,” “The Artist’s Daughters with a Cat,” or any of his other portraits of his girls, they must really know Gainsborough’s work and will better understand the theme of this novel. This is Emily Howes’ first book and in it she focuses on the bonds between Mary and Margaret Gainsborough, more familiarly called in this book by their nicknames, Molly and Peggy. By focusing on the girls, Howes is able to conjure up images of the family life of the 18th century British painter and explore the close bonds that existed between the two girls for most of their lives.

The early scenes take place in Ipswich in Suffolk, where the girls chase butterflies, pick blackberries, and play around the chicken coop in a very rural setting. Although Molly is the older child, it is Peg who first recognizes that something is wrong with her sister, who occasionally slips into trances that she never remembers and who sleepwalks around the house and even outside. The girls’ mother, Margaret, is much less tolerant of their shenanigans and Peg begins to lie to protect Molly. Their mother urges Thomas to move to the city of Bath, where she thinks the girls will be less likely to act as wildcats, and where Thomas is more likely to find wealthy patrons desiring his paintings. Both girls preferred living In Ipswich, but they gradually adjust to life in a city. Peggy carries sisterly love to the extreme as she repeatedly intervenes to cover for Molly’s “episodes” by rushing to her side and squeezing her hand until she snaps out of them, all the time hiding Molly’s problems from their parents. Peggy could never have imagined that she would be assuming responsibility for her sister for a lifetime.

The author traces the girls’ experiences beautifully as they duck in and out of their father’s studio and play with each other. Thomas’ business improves, but the family’s financial resources continually depend on his painting of portraits, even though he much prefers landscapes, and should he become very ill or die, his family will have a difficult time surviving. The girls’ mother Margaret does have some money, but not enough to pay for all expenses for very long. Thomas hopes to teach Peggy, whom he affectionately calls “Captain,” but this does not work out. He then plans to bring his nephew into the family as his apprentice and the girls deeply resent the boy’s presence.

Peggy narrates most of the chapters, but interspersed among these are chapters by someone called Meg Grey, whose connection to the Gainsboroughs is only revealed late in the book. The girls often wonder why their interactions with family members always seem to be with their father’s relatives and not with their mother’s, but the answer to this is also held in suspense. There are a few references to tutors coming to their house to instruct the girls, but I thought that their education should have received more attention. The girls are closer to their father, and their mother often becomes very angry at their actions, but it soon becomes obvious that she is driven by high hopes that they will both move up in society and marry well.

Meg Grey’s chapters are set in Harwich in Essex at first, where her father runs a pub. Her chapters shift to London later on, as do Peggy’s when the painter’s family moves from Bath to London. Meg’s story focuses on her desire to get away from her father and care for the child she is about to bring into the world, without a father or resources to provide them food and shelter for the future. The difficulty of moving anywhere in life in the 18th century, when most travel is by walking or, if lucky, by carriage, is quite obvious. Throughout the novel, Howes does a marvelous job of bringing readers into the house and studio of Thomas Gainsborough and helping them feel what life holds for his two girls.

The author explains in her notes that she has changed the date on one event to benefit the story and explains why she has chosen to include some events or interpretations of the real people she covers. I noted that Howes has Meg’s father refer to Frederick of Hanover, the son of King George II and father of King George III of England, as Prince of Wales in 1728, when in reality he didn’t receive that title until early in 1729, but this is a small issue. Overall, “The Painter’s Daughters” is an excellent, rich, and pleasing historical novel. I recommend it very highly.

– Reviewed by Richard Weigel, WKU History Department