Book review: ‘Invention: A Life’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, April 10, 2022

- BOOK REVIEW

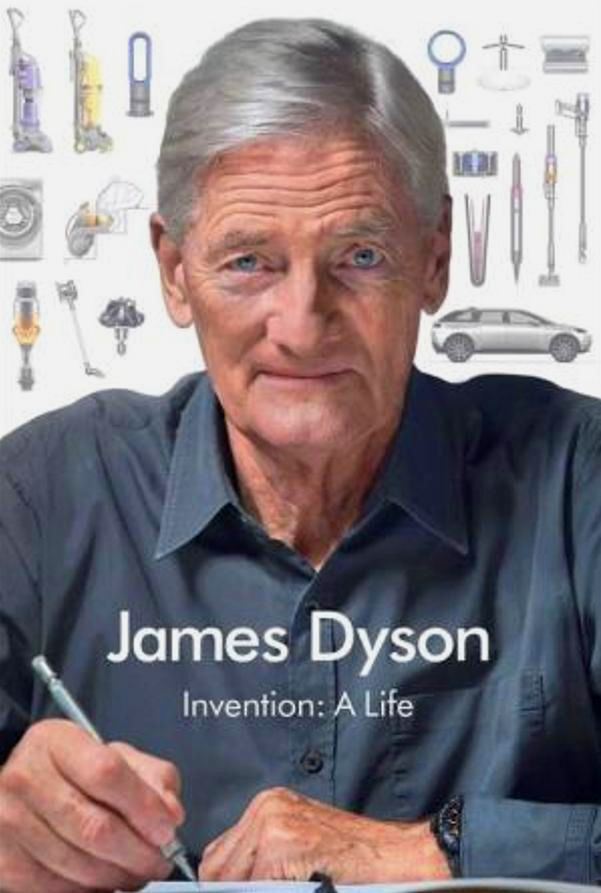

“Invention: A Life” by James Dyson. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2021. 384 pages, $30 (hardcover).

“In 1983, after four years of building and testing 5,127 handmade prototypes of my cyclonic vacuum, I finally cracked it,” James Dyson explains in “Invention: A Life,” his autobiography. “Perhaps I should have punched the air, whooped loudly and run down every road from my workshop shrieking ‘Eureka!’ at the top of my voice. Instead, far from feeling elated – which surely after 5,126 failures I should have been – I felt strangely deflated.

Trending

“How could this have been?” he continues. “The answer lies in failure. Day after day, with the wolf at the door, I had been pursuing the development of an ever more efficient cyclone for collecting and separating dust from a flow of air. I built several cyclones each day, conducting tests on each one to evaluate its effectiveness in collecting dust as fine as 0.5 microns – the width of a human hair is between 50 and 100 microns – while using as little energy as possible. This might sound boring and tedious to the outsider. I get that. But when you have set yourself an objective that, if reached, might pioneer a better solution to existing technologies and products, you become engaged, hooked and even one-track-minded.”

So begins one of the most fascinating forays into the creative process I have ever had occasion to peruse. Sure, as is expected with any memoir, Dyson provides the requisite story of his significant personal relationships – starting with his father who died of prostate cancer when he was 18 – and how his upbringing ultimately shaped him into one of the most successful businessmen in history. And I found that aspect of his life mesmerizing.

“I remember my father as an ever-cheerful polymath,” Dyson recalls in “Growing Up,” the inaugural chapter. “He ran the school cadet force as a major, coached hockey and rugby, and taught me to sail dinghies on the Norfolk Broads. He used to wake me up early in the morning to catch the spring tide down at Morston. He did so following a stormy night in 1954 when the sea floods had swept across the mudflats, marshes and valleys of north Norfolk. This wasn’t a matter of simply jumping in the car and speeding out to find the boat. Our car, an old Standard 12, powered by a Jaguar engine, if I recall, demanded a hand-crank start with a violent kickback and suffered frequent breakdowns. It was certainly an adventure.”

But it was his in-depth treatment of the intricacies of the creative process, together with the insights he provides for those aspiring to follow in his footsteps, that I found truly captivating.

“I love the fact that we tackle ordinary products, making the vacuum cleaner into a high-performing machine,” the author notes in “DC01,” the sixth chapter and one of my favorites. “As we did, we developed Dyson into a tech company driven by the very graduate engineers we took on. We quickly built up a team and what we began to think of as campuses of brilliant young engineers who understood that their job was to think freely, ask questions and challenge what we did to find better design, technology and products.

“The stories and people behind these machines show what’s possible when engineers think big, unconstrained by the current state of the art,” he continues a paragraph later. “They can really change the world. Our machines are not museum artifacts; they’re here to be touched and understood in terms of the ideas behind them, the engineering that made them possible, and the frustration and failure that went into them along the way.”

Trending

Structurally, the book consists of an introduction, 12 relatively dense (in a good way) chapters and postscripts by Jake, his son who is an industrial designer, and Deirdre, his wife who creates and produces high-end carpets and rugs. The manuscript is beautifully illustrated with a number of technical drawings and graphics that serve to bring the narrative to life in a way that would have been somewhat difficult to do otherwise. Honestly, if you want to know what makes his products so demonstrably superior to those of his competitors, you will leave this volume thoroughly versed in the innovations that have become synonymous with his brand.

The chairman and chief engineer of Dyson Ltd., the company best known for the revolutionary cyclonic vacuum cleaner, Dyson studied design at the Royal College of Art in London before joining Rotork to help produce – along with Jeremy Fry – the Sea Truck, a high-speed, flat-bottomed boat. His first original invention was the Ballbarrow, a modified version of a wheelbarrow using a ball instead of a wheel. The recipient of several prestigious honors and awards, including being appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire, he is currently the fourth-richest person in the United Kingdom.

Full disclosure: The book can be somewhat challenging in places as the prose does tend to lean heavily toward the technical with some of his explanations. But I was able to navigate most passages with a little reflection and maybe a visit or two to Google. My sense is that most readers would be able to decipher those sections with minimal effort and develop an even greater admiration of the man who added convenience, efficiency and especially cleanliness to many of our lives.

Incidentally, I found Dyson’s take on education to be eerily similar to my own, especially when he articulates his criticism of a dimension of the formal learning process that I have found troublesome for decades.

“Children love making things and yet, all too often, this innate curiosity and experimentation expressed through our hands is stamped out by the educational systems that see no virtue in such natural creativity,” he writes in “Education,” the 11th chapter. “Because parents and schools are driven to get children through school and into college, and because the educational system is geared – notably in Britain, the nation that triggered the Industrial Revolution – to cerebral subjects, the making of things is considered a waste of time as pupils face the challenge of exams.”

Amen and déjà vu. Highly recommended.

– Reviewed by Aaron W. Hughey, University Distinguished Professor, Department of Counseling and Student Affairs, Western Kentucky University.