Book review: ‘Led Zeppelin’

Published 12:15 am Sunday, December 12, 2021

- BOOK REVIEW

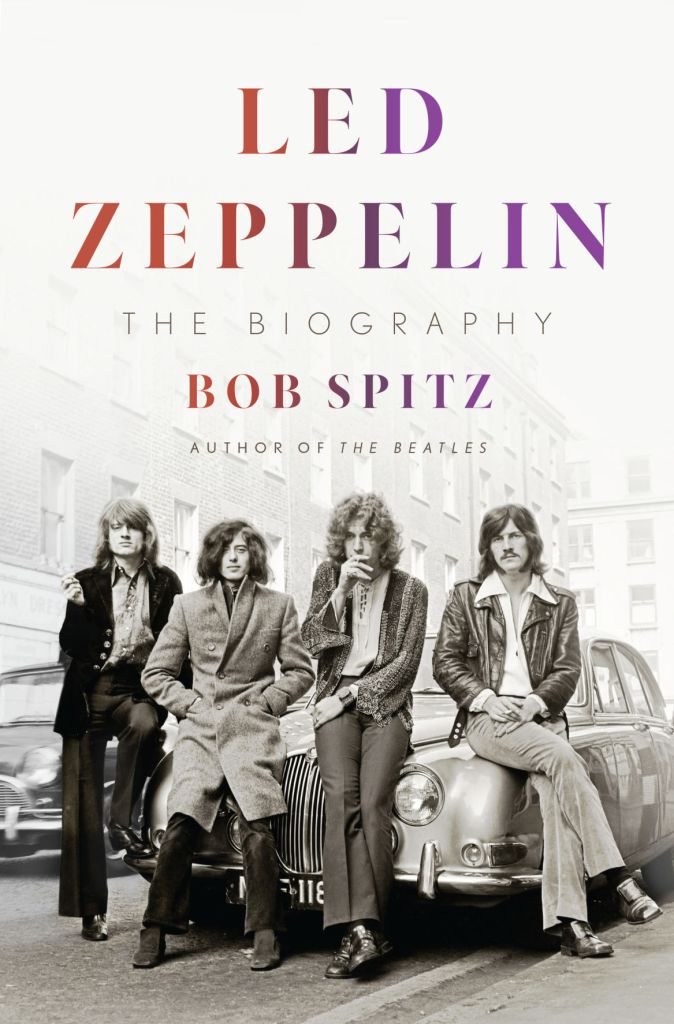

“Led Zeppelin: The Biography” by Bob Spitz. Penguin Press. 688 pp. $35. Review provided by The Washington Post.

Depending on whom you ask, Led Zeppelin embodied either the best or worst of rock ‘n’ roll. The band – Robert Plant, Jimmy Page, John Paul Jones and John “Bonzo” Bonham – epitomized either the dreamy idealism of the 1960s or the bloated vapidity of the 1970s. It was either an appreciation of blues and folk or a wholesale theft of those genres.

While critically underappreciated for the 12 years it existed, Led Zeppelin’s art has since been both revered and mocked. It’s generally accepted that punk rock was – to a degree – a response to what many saw as the self-indulgence and pompousness of the band and others of its ilk who shared a proclivity for stadium spectacle and extended drum solos. The 1984 satirical rockumentary, “This Is Spinal Tap,” was inspired in part by the same aspects; the film got some of its biggest laughs by utilizing Led Zeppelin’s absurd 1977 Stonehenge stage set. Today, few deny the artistic value of the group’s catalogue, but it would be an understatement to say that the Led Zeppelin’s history is complicated.

The cheeky subtitle of Bob Spitz’s new book “Led Zeppelin: The Biography” is bold considering the numerous books about the band. Spitz, who has written well-regarded biographies of the Beatles and Julia Child, delivers a 600-page tome that collects every (reliable) story previously reported, and is bolstered by original reporting and interviews – all delivered in brisk and straightforward prose. But readers be warned: Spitz doesn’t hold back in describing the band’s antics, its displays of ego and cruelty that today’s audiences might find less than acceptable.

The book begins with a witty prologue chronicling what it was like for a young Steven Tyler (later of Aerosmith and being Liv Tyler’s dad) to see the band that arguably invented heavy metal play the heavy, progressive blues that it didn’t invent but exemplified. The prologue is breathless and slangy, befitting the point of view of a hormonal rocker having his mind blown. It’s cute. The reader is happy for Steven Tyler.

Then the book gets serious. “In the beginning there was the blues,” Spitz intones, before jumping right into postwar England and recounting the seismic effect the blues had on the country’s nascent youth culture. The book is peppered with musical references that Spitz describes as evocatively as mere writing can describe music and cultural references (at one point Spitz says that a manager of the Yardbirds had “his fingers in as many pies as Mrs. Lovett”) that may cause some readers to fall into a rabbit hole of music minutia. It may cause others to give up.

Spitz is admirably unsparing, without being egregiously harsh, in his assessments of the attempts by White British musicians to approximate the sounds coming from imported, eagerly collected records by legends such as Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters. When American blues musicians start touring the U.K., the joy felt by wide-eyed young Eric Claptons and Jimmy Pages is contagious. Also contagious, at first, is Spitz’s affection for the book’s main subjects. At first, all four men who formed Led Zeppelin are lovable. Whether it’s Page and Jones’ Zelig-esque studio work (the number of pop classics Page in particular worked on before becoming famous never fails to impress) or Bonham and Plant striving as a working-class mid-country bar band, the reader is pulling for each of them.

But after Led Zeppelin forms, or at least once they gain even a modicum of success, little is endearing about any of the band members besides the music they make. Once the group’s thuggish manager, Peter Grant, enters the picture and it becomes clear, over and over, that nobody will tell him or any member of the band “no” for the next decade, human decency joins the hotel televisions in going out the window.

Many people might insist on separating the art from the artist or believe that ethics in touring culture can occasionally be situational. But the stories Spitz unearths and reiterates about what Led Zeppelin and their entourage got away with are, even to readers jaded to bad celebrity behavior, appalling. Many anecdotes in “Led Zeppelin” inspire a visceral disgust – sexual violence and other crude behavior that can’t be detailed in a family newspaper. Spitz delves into some of the more infamous incidents, adding new details that make these tales ever more shocking. The reader is frankly relieved when the band eventually settles into the banality of inconsistent live shows and tax troubles.

Spitz’s handling of all this is patchy. At times, he denounces. At times he equivocates. At times, he slyly hints at judgment at the band’s various inanities and unsavory behavior. He lets Robert Plant’s famous proclamation of “I am the golden god” lay flat on the page in a way that allows the idiocy to speak for itself. He follows Lori Mattix’s name repeatedly with “the 14-year-old,” so that even the most fervent Jimmy Page fan is hopefully forced to reckon with the guitarist’s relationship with a teen. As for Mattix herself (also known as Lori Maddox), readers will have to look elsewhere to hear her complicated, evolving perspective on her own experience.

Sure, Spitz allows, not all of the band members or roadies preyed on teenage girls, and defecated and urinated on fans, but all were at various times either complicit or, at best, voyeurs to a nauseating level of violence and degradation. And, yes, even in the context of the times. While there are numerous available examples of rock stars behaving in similar fashion as the members of Led Zeppelin, there were plenty of musicians in the 1960s and 1970s who were aware that women, even young women, were human beings. Buffy Saint-Marie, who was arguably as innovative as Zeppelin in her work within folk traditions, never degraded her fans. The Monkees were famously sweet to their legions of fans. Even the inventor of shock rock, Alice Cooper, is considered (as described in Michael Walker’s excellent “What You Want is in the Limo”) to be a nice guy. It was possible.

“Led Zeppelin: The Biography” was written without the cooperation of any surviving members of the band. It’s hard to blame them. While largely admiring in tone, no grisly detail is omitted – and who would want to answer for any number of the stories told, especially when, in 2021, young and extremely high is no longer considered exculpatory. Even without the assistance of Led Zeppelin or its inner circle, Spitz manages to tell a compelling story (despite a few factual errors in my edition). The music criticism is often insightful and evocative: Spitz describes the bass in “Good Times, Bad Times” as pulling “at the center like an undertow,” and Robert Plant’s singing as “otherworldly, like it was coming out of a pneumatic compressor.”

The world Led Zeppelin inhabited is fascinating. But without the protagonists’ input, the center feels incomplete – sketches within a painting. John Paul Jones comes off best by not coming off at all. Robert Plant’s feckless pliancy throughout is hard to square with the exploratory nature of his later work. Jimmy Page comes off as a caricature of not-exactly-dumb-but-hardly-smart mystical libertarianism. John Bonham and Peter Grant, both dead, are portrayed as designated monsters.

The book ends abruptly, with sputtering reunion attempts and amiable charity gigs. Fans and naysayers alike will be disappointed that in Spitz’s telling nothing any of the men did after Led Zeppelin broke up seems to warrant much discussion. As a compendium of the often brilliant music created by ravaged souls, the book works well enough, but at this point both Led Zeppelin’s fans (and critics) yearn for more.

– Reviewed by Zachary Lipez, who has co-authored (with Stacy Wakefield and Nick Zinner) a number of books of essays, poetry and photography.