Book review: ‘Little Sister’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, November 21, 2021

- BOOK REVIEW

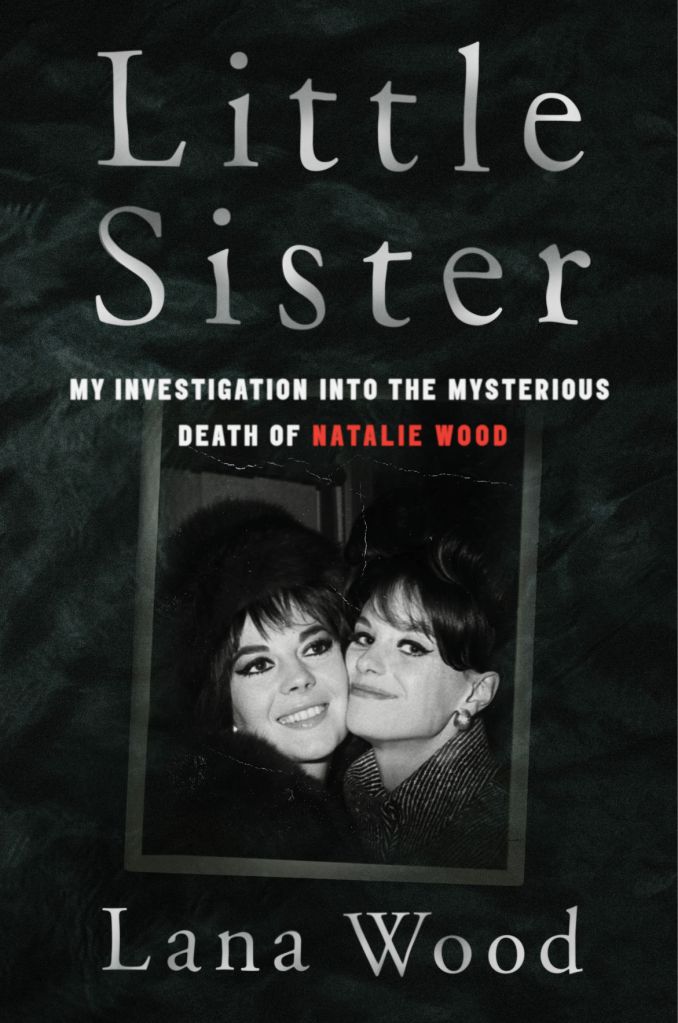

“Little Sister: My Investigation into the Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood” by Lana Wood with Lindsay Harrison. Dey St. 238 pp. $27.99. Review provided by The Washington Post.

The story of Natalie’s Wood’s death has been replayed countless times in tabloids, interviews and on television. Police and autopsy reports can be read online, and there have been numerous books, including last year’s “More Than Love” by Wood’s daughter Natasha Gregson Wagner, which accompanied a splashy HBO documentary. Still, 40 years after Wood’s body was found floating in the water near her yacht off Catalina Island, the circumstances of her death remain unresolved.

Trending

Lana Wood, Natalie’s younger sister, has jumped into the mix with a book whose title – “Little Sister: My Investigation into the Mysterious Death of Natalie Wood” – promises some answers. Now in her 70s, the one-time actress and producer feels compelled to break her silence. “Telling this story is the bravest thing I will ever do,” she pronounces in the book’s opening pages.

Lana Wood begins with the gossipy backstory of Natalie Wood’s rocky marriage to Robert Wagner in 1957. Lana is very sour on that relationship, focusing on a pivotal moment: “It seems she’d come home early from somewhere, poured herself a glass of something, and walked into her and (Wagner’s) bedroom to find him in a very compromising position with his butler.” Lana, who already shared much of this material in her 1985 memoir “Natalie, A Memoir by Her Sister” dishes about Natalie’s relationships with Warren Beatty (her co-star in “Splendor in the Grass”), Michael Caine and others. Natalie then married British producer Richard Gregson, father of her daughter Natasha. They divorced in 1972. Later that year, Natalie and Wagner remarried.

Lana Wood was enraged about her sister’s reconciliation with Wagner. “I hit the roof,” she recalls. “She was remarrying a guy who had cheated on her with another man? I’d been through something similar when I walked in on one of my ex-husbands trying on my favorite peignoir.” (Lana, who played Plenty O’Toole in the Bond film “Diamonds Are Forever,” doesn’t hold back.) Natalie’s response was more ominous. “Sometimes the devil you know is better than the devil you don’t.”

In her book’s one real bombshell, Lana alleges a trauma from Natalie’s teenage years: how 15-year-old Natalie was assaulted by Kirk Douglas during what was said to be an audition, while her mother and little sister waited in a car near his hotel. Lana says their mother told Natalie to keep it quiet or it would mean the end of her career. “I was more enraged at mom than I was with Kirk Douglas,” Lana writes. “She’d sent her 15-year-old daughter into a hotel room alone with an incredibly powerful man … and then done absolutely nothing when he violated her.”

Lana then delves into the oft-treaded material of the fateful 1981 Thanksgiving weekend when Natalie and Wagner embarked on a cruise to Catalina Island on their yacht, Splendour. Also onboard were Christopher Walken, Natalie’s co-star in what was to be her final film, “Brainstorm,” and skipper Dennis Davern, later demonized by the tabloid press as the “death yacht captain.”

“Little Sister” presents the various, often contradictory narratives of what happened that Saturday night, compiled from witnesses and police reports.

Trending

Lana’s storytelling can be confusing, with its crosshatch of conflicting and recanted accounts, family memories and her own familial woes, which include the death of her daughter, Evan, in 2017. But the upshot is clear: Lana Wood blames Robert Wagner (known as R.J.) for her sister’s death. “I have no trouble imagining R.J., five-foot-eleven, two hundred pounds, and Natalie, five-foot-two, one hundred twenty pounds, fighting back, first in their stateroom, where Dennis heard enough yelling and banging to knock on the door and be told by R.J. to ‘go away,’ and then on the back of the boat.” Lana, who is estranged from Wagner and Natasha Gregson Wagner and refused to participate in the HBO film, says it pains her to believe that R.J. would hurt her sister: “What possible pleasure could I take in thinking that the last thing my sister saw in this life was the furious face of her husband, hovering above the dark water that terrified her?” The answer, alas, comes shortly thereafter when she accuses Wagner of shutting her out of the family and “allegedly blacklisting me in the business,” among other things.

Still, “Little Sister” lists persuasive circumstantial evidence that Natalie’s death might not have been an accident. In 1992, Lana was contacted by Davern, who intimates that Wagner harmed Natalie before her death. This news galvanizes Lana into turning amateur detective. She obtains a copy of the police report and is struck by witness statements that appear to have been dismissed by the police. The manager of the restaurant where the Wagner party dined that night “thought at the time there were some possible problems between Robert Wagner and his wife.” A harbor patrol officer stated receiving a call from a couple onboard a vessel near the Splendour who reported that “they’d heard a female screaming for help around midnight.” The husband said the woman sounded drunk. His wife thought she sounded hysterical. After Natalie’s body was recovered, it was Davern who identified it, rather than her husband. The paramedic who pulled Natalie’s body from the water was never interviewed.

“This was definitely more complicated than ‘an accident,’ ” Lana decides, and wonders why the case was immediately closed.

Lana has consulted with a retired LAPD detective who she says agrees that much of the initial investigation was mishandled, in particular the fact that no forensics were done. Still, despite the promise of Lana’s title, she doesn’t really deliver any new information relating to her sister’s death, and her estrangement from Natalie’s family results in a constant background din of axes being ground. Discovering the truth seems an impossible task even now. Ultimately, Natalie Wood’s death resembles a Rashomon for the #MeToo era – multiple people telling the same story, with no consensus as to what actually happened.

– Reviewed by Elizabeth Hand, whose novel “Hokuloa Road” will be published next year.