Book review: ‘Black Lives Matter at School’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, April 25, 2021

- BOOK REVIEW

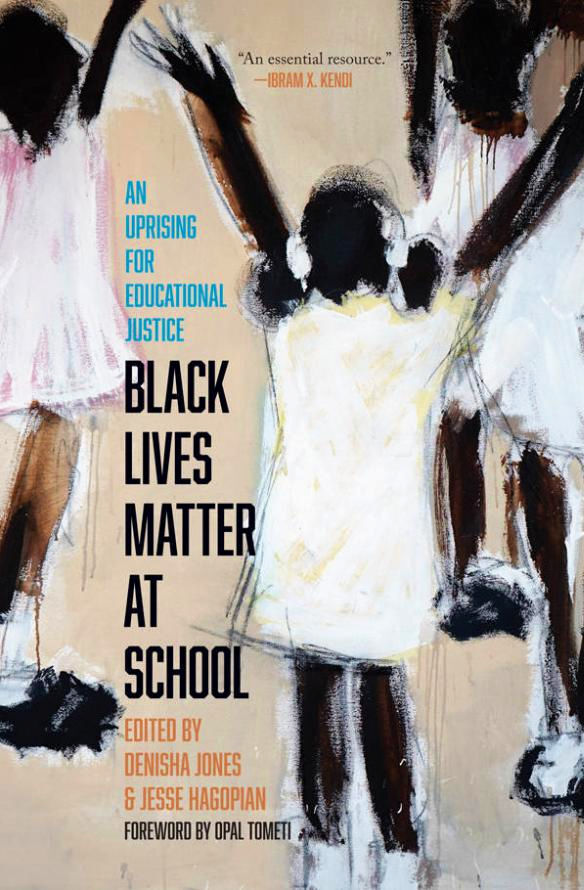

“Black Lives Matter at School: An Uprising for Educational Justice” edited by Denisha Jones and Jesse Hagopian. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2020. 300 pages, $24.95 (paperback).

“In the late 20th century, Black college students rose up all over the United States, demanding the formation of Black studies and ethnic studies departments on their campuses,” Brian Jones explains in “Black Lives Matter at School: Historical Perspectives,” the second chapter of “Black Lives Matter at School: An Uprising for Educational Justice,” the new edited volume by Denisha Jones and Jesse Hagopian. “From historically Black colleges like Tuskegee Institute in Alabama to Ivy League institutions like Brown University, students in the 1960s and 1970s protested, sat in, occupied buildings and more, with a wide range of demands that almost always included the teaching of Black history and the mandating of Black studies in some form.

“When a majority of the students at San Francisco State College went on strike in 1968, they won the formation of the nation’s first Black studies department as part of a new School of Ethnic Studies,” writes Jones, who is associate director of education at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem.

Building on the energy of the movements of the 1960s, Black parents, educators and activists developed regional and national networks of independent Black schools in the 1970s that put Black studies at the core of their mission.

“Black Lives Matter at School” is comprised of 30 chapters by 31 contributors arranged in five major sections: “Introduction,” which consists of the first two chapters; “The Start of a Movement,” which is made up of the next three chapters; “Securing Union Support: Successes and Struggles,” the next five chapters; “Educators Doing the Work,” the most comprehensive section with 12 chapters; and “Voices of Students,” the final eight chapters. A feature I especially enjoyed was the inclusion of several applications-oriented “Features” scattered throughout the narrative, such as “Not Just in February! Reflections to Make Black Lives Matter Every Day in Your Classroom,” which is sandwiched between chapters 21 and 22. I also found the Epilogue, “Inequity and COVID-19” particularly interesting and relevant to the current situation in this country.

A central theme winding its way through many of the essays is the “Week of Action,” which is a tangible mechanism for precipitating fundamental change; i.e., translating the ideas presented in the book into reality. “Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action is a time set aside to affirm all Black identities by centering Black voices, empowering students and teaching about Black experiences beyond slavery,” Coshandra Dillard notes in “Teaching Tolerance.” “The lessons emphasize social justice and ethnic studies, but in addition to classroom work, teachers like Hagopian are organizing, planning, protesting and addressing real-world issues that affect Black students.” This year marks the fourth time the event has been held at the local, regional and national level.

If you want to know why many in the educational community are so passionate about expanding the curriculum to be more inclusive and relevant to the personal experiences of an increasing number of our nation’s citizens, this is a primer you will definitely want on your bookshelf. Jones and Hagopian have assembled a compendium that serves as an invaluable resource for anyone who wants to know why our educational system has been woefully – and deliberately – deficient in meeting the needs of the most vulnerable among us. More importantly, the collaborators on this exquisite and extremely insightful collection offer a variety of perspectives from across the social, cultural and academic spectrum that need to be heard. I learned a great deal from the diverse viewpoints espoused by these talented and brave writers.

For example, “White Educators for Black Lives,” the 18th chapter, really hit home with me. Although a relatively short read, I nonetheless found the ideas articulated by Rosie Frascella, B. Kaiser, Brian Ford and Jeff Stone to be especially instructive and even profound:

“ ‘If you put a chain around the neck of a slave,’ Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote, ‘the other end fastens itself around your own.’ Emerson was the author of a number of anti-slavery essays, but he also expressed racist ideas elsewhere in his writing, most notably in ‘English Traits.’ Emerson is an example of the tension we hold as White people: espousing abolitionist, antiracist views (and acting on them), while at the same time retaining internalized racist ideas absorbed from a racist society. Emerson’s words additionally capture how White folks in a racist society are themselves not free. Just as a patriarchy harms men, racism and anti-Blackness constrain the minds of White people, leading them to invest in the idea of their supposed Whiteness, which is really just a relationship to power. To live in a world that upholds Whiteness and White supremacy is to be unfree.”

A member of the Black Lives Matter at School Steering Committee and director of the Art of Teaching, the graduate teacher education program at Sarah Lawrence College, Jones has a B.S. in early childhood education and a certificate in nonprofit leadership from the University of the District of Columbia, a J.D. from the University of the District of Columbia, and a Ph.D. in curriculum and instruction from Indiana University. Hagopian, who is also on the Black Lives Matter at School Steering Committee, is an editor with “Rethinking Schools” as well as a high school teacher at Garfield High School in Seattle, Wash., where his specialty is ethnic studies. A co-adviser to the Black Student Union at Garfield, his undergraduate degree is from Macalester College; his resume includes a master’s degree in teaching from the University of Washington.

I believe many readers would find “Black Lives Matter at School” to be an eye-opening exploration of the educational dimension of a movement that has been mischaracterized by many in the media. When you consider the inclusive vision these passionate, committed and decidedly nonviolent educators have for the future they are trying to create, I believe you will be more empathetic – and less dismissive – of their cause. Highly recommended.

– Reviewed by Aaron W. Hughey, University Distinguished Professor, Department of Counseling and Student Affairs, Western Kentucky University.