Book review: ‘OK Boomer, Let’s Talk’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, August 23, 2020

- BOOK REVIEW

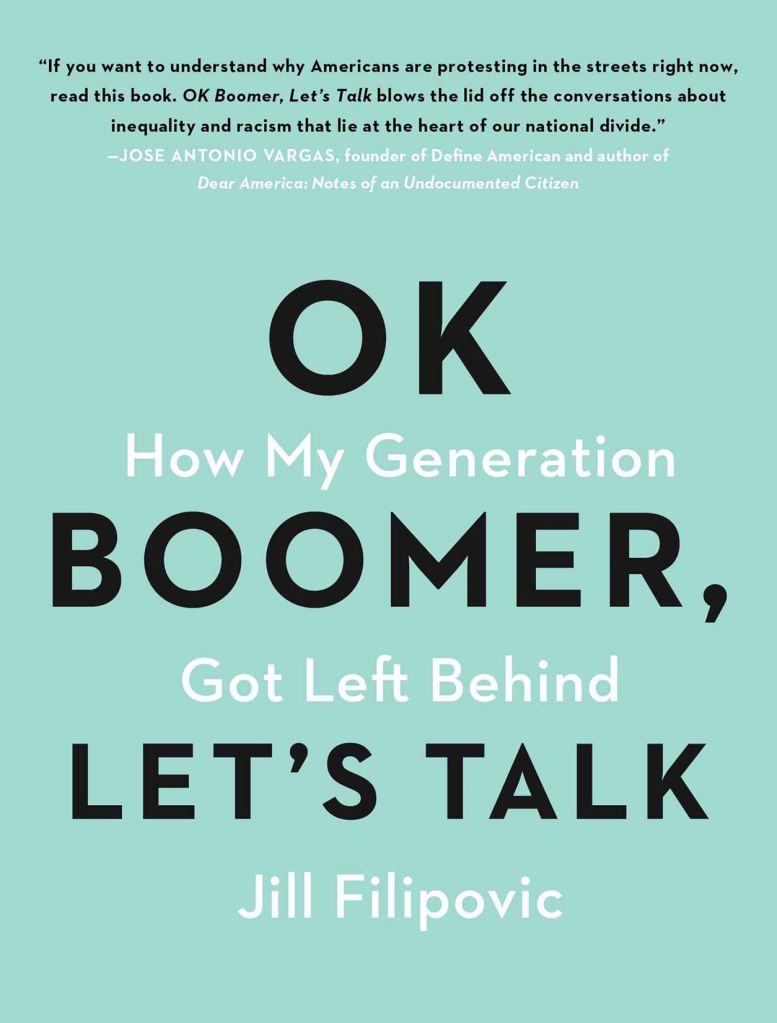

“OK Boomer, Let’s Talk: How My Generation Got Left Behind” by Jill Filipovic. Atria/One Signal. 325 pp. $17 paperback. Review provided by The Washington Post.

About one million years ago, in 2019, the long-simmering generational tension between the baby boomers and the millennials exploded into meme combat: The internet was alight with cries of “OK boomer,” as younger generations issued a collective eye roll to their boomer parents. In her new book, “OK Boomer, Let’s Talk,” author Jill Filopovic explains what she sees as the root of the tension: Millennials are leading different – and often worse – lives than their parents did, and boomers are to blame.

“A true reckoning with the consequences of Boomer policies and decisions casts a harsh light on the children of the Greatest Generation,” she writes, adding that this book is that needed reckoning and, as she puts it, “a peace offering to those Boomers who are worried about the world they’re leaving their children.”

The reckoning is long overdue. America is in the midst of a generational turnover, one that has the power to reshape our economy, family structures and the fundamental social contract we make with our government. And in a time of massive income inequality, social unrest and political upheaval, it’s hard not to blame the generation that has been at the steering wheel for the past 30 years. It can sometimes feel as if Mom and Dad bought a wood house, decorated everything with paper, dismantled the sprinkler systems, lit a match and now wonder why their kids are screaming that the house is on fire.

We already know that millennials are more socially tolerant than their parents, more likely to support big government action on climate change and health care and less likely to own homes and start families than boomers were at their age. This book explains the data behind those trends, laying out how, as Filipovic puts it, “life at 30 for your average Millennial looks close to nothing like life at 30 did for you.” “OK Boomer” is structured according to topic – jobs, housing, climate, family, etc. – and each section includes research on how millennials have experienced each corner of adult life differently than their parents did. If you’re getting ready for generational combat on your family Zoom calls, consider this book your handy arsenal of easily weaponized facts.

Filipovic is particularly smart on issues of gender, relationships and the inequality of labor at home, and the sections of “OK Boomer” that interrogate how millennials are having different kinds of sex, renegotiating marriage and children, and re-creating the nuclear family are especially sharp. And her research into how Fox News has poisoned the minds of many TV-addicted boomers is particularly relevant in an election year when the president is relying on support from aging white baby boomers. This book is full of data – on the economy, technology and more – that will help millennials articulate their generational rage and help boomers understand where they’re coming from.

But Filipovic doesn’t quite successfully prosecute the case against boomers, nor does she offer a fresh analysis of millennials’ generational destiny. Instead, she presents research to prove what has by now become common knowledge: that millennials are more indebted, more financially precarious, more concerned about climate change and less personally and professionally secure than their parents were. And while Filipovic is right that many of our most pressing national issues can be viewed through a generational lens, she too often slips into tangents about other cultural issues, from wellness trends to Roman Polanski, that seem only thinly connected to the central generational conflict. Some problems that she presents as uniquely millennial – like moving to a cheaper area to raise a family or sacrificing passions for job security – are simply the sour trade-offs of adulthood, which boomers and Gen Xers have grappled with as well. At times, “OK Boomer” feels less about the divide between boomers and millennials, and more about everything that is wrong with everything.

That may be the point. Filipovic argues that nearly every systemic problem in America – from unaffordable housing to a broken health care system to the difficulty of raising a family – is the fault of the baby boomers. While boomers often take credit for the social movements of the 1960s, she points out, those movements were largely led by non-boomers born in the 1920s and 1930s (although all leaders need followers, and many of those followers were boomers). Baby boomers’ true political legacy, she argues, is the Reagan revolution of the 1980s and the shrinking of the social safety net in the decades that followed (although while many boomers voted for Ronald Reagan, they’re hardly solely responsible for his presidency – he won in a landslide, across all generations, both times). But on the whole, Filipovic is right that boomers have fumbled the generational football: They didn’t address climate change when they could, gutted public investment in social programs that would have benefited their children and grandchildren and ushered in a new era of economic precarity that left their descendants poorer and more anxious. Older white voters – many of them boomers – are directly responsible for the Trump presidency, which might be considered the lighted match in the paper house.

But while it’s true that boomers have largely failed to create a better world, Filipovic risks overstating the exact scope and nature of that failure and ends up laying the entirety of American social injustice at their feet. It’s true that boomers haven’t lived up to their self-professed 1960s ideals that they could have done more to achieve racial justice and gender equality, and that significant gaps still remain. But America is significantly less racist and sexist in 2020 than it was when the first boomers were born in 1946, when they joined the social movements of the 1960s and ’70s, or even when they reached political maturity in the 1980s. Throughout this book, Filipovic falls into the particularly millennial habit of equating inadequate progress with total failure: True, boomers didn’t create a perfect world for their children, but they didn’t inherit a perfect world from their parents, either.

– Reviewed by Charlotte Alter, who is a national correspondent at Time.