Book review: ‘Savage Appetites’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, September 1, 2019

- BOOK REVIEW

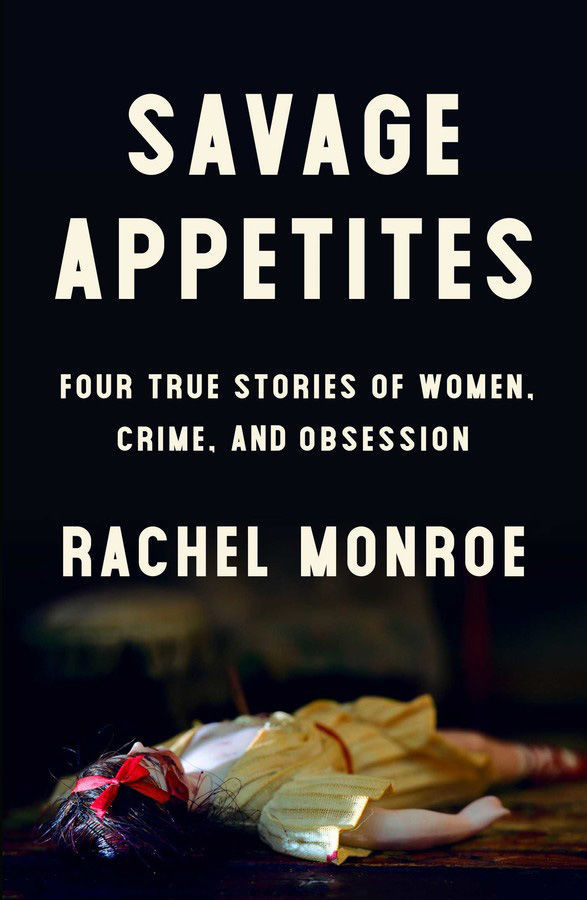

“Savage Appetites: Four True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession” by Rachel Monroe. Scribner. 257 pp. $26. Review provided by The Washington Post.

In 2007, the writer Maggie Nelson invented the term “murder mind” to describe her attraction to stories of violent death and the tendency of bloody images to stick in her brain. Today, our entire culture might fit her diagnosis.

True crime has never been more ubiquitous as entertainment. The blockbuster popularity of the podcast “Serial” and docuseries such as Netflix’s “Making a Murderer” have spawned an endless succession of imitators. So recognizable are the rhythms of the genre that they’ve even inspired a boomlet of parodies (see: “American Vandal,” “A Very Fatal Murder” and “Done Disappeared”). The floundering Oxygen network reversed its fortunes in 2017 when it rebranded to air exclusively true crime.

What accounts for the inexhaustible appeal of watching someone – an attractive, young white woman, usually – get asphyxiated, dismembered or stabbed? In particular, why do so many women, who make up most of the true-crime audience, seem to find comfort in seeing their worst fears play out on a screen? Over the years, cultural critics like Nelson and Alice Bolin, author of the acclaimed essay collection “Dead Girls,” have searched for answers in the stories we tell about murder. In a new book, “Savage Appetites: Four Stories of Women, True Crime, and Obsession,” the journalist Rachel Monroe employs a more reportorial approach, seeking subjects with an extreme passion for true crime. One falls in love with a man on death row, while another plans a Columbine-style killing spree.

By looking at women looking at violence, Monroe doesn’t quite answer the question of why women love true crime – as she points out, women are a diverse group with a wide variety of motivations. Instead, she ends up with something subtler and more useful, a call to action for crime-heads to consume the stories they want, but to do so critically. She delivers a defense of the genre that is also an indictment of its worst impulses.

“Sensational crime stories can have an anesthetizing effect – think of those TV binge-fests, or late nights spent tumbling down a Wikipedia rabbit hole – but we don’t have to use them to turn our brains off,” Monroe writes. “I want us to wonder what stories we’re most hungry for, and why; to consider what forms our fears take; and to ask ourselves whose pain we still look away from.”

Monroe’s “we” is genuine: She herself is prone to what she calls “crime funks” when she loses herself in obsessions with murder. Each chapter contains passages that interrogate her own appetites. In one, she weaves together the story of Frances Glessner Lee, known as the “mother of forensics,” with her own pre-adolescent dream of becoming a detective. During the unnerving years when men began to notice her body, Monroe writes, novels about hard-boiled sleuths were the only books that “acknowledged the sexualized menace of the world.” Monroe is a perceptive narrator, and I sometimes wished for more of her personal story, which produces many of the book’s best insights but often peters out inconclusively. We learn how Lee’s ambitions were foiled but not how a young Monroe’s faded away.

The four subjects of “Savage Appetites” represent four archetypes of true-crime narratives: While Lee was obsessed with detectives, the other women identify with victims, killers or selfless attorneys. Their stories span not only a genre, but also the country and the past century. At their most engaging, they offer a piecemeal history of our culture’s changing view of violence.

The strongest chapter, and the most skin-crawling, follows a woman named Alisa Statman and her fixation on the Manson family’s most famous victim, actress Sharon Tate. Statman took up residence first on the property where Tate was murdered and later with Tate’s sister in her family home. In the process, Statman and the surviving Tates became foundational forces in the victims rights movement of the 1980s and 1990s, which successfully campaigned for “tough on crime” policies. Monroe connects the appeal of true-crime stories, which run “on an engine of empathy,” with the persuasive power of the victims’ rights movement, which encouraged onlookers to put themselves in a murdered girl’s place. But the faces of the movement were almost always those of white women. And black men were often victims of this cult of victimhood, incarcerated at unprecedented levels – including for nonviolent offenses – under policies that got a push from stories like Sharon Tate’s.

“The danger of a politics of empathy is that our own biases are built-in, from the foundation up,” Monroe writes. “Pain that looks more like our pain is easier to imagine as real, as painful.” True crime rarely covers the people who are most likely to face deadly violence, such as young black men and transgender women of color. Monroe pays close attention to what the genre teaches us to feel and for whom.

Other chapters introduce us to different crime trends in recent history: the Satanic Panic of the 1970s and 1980s, the shoddy forensics that took off in the 1990s and the active-shooter terror of our present day. These wider-lens narratives are fascinating and frightening, more revealing in some ways than the portraits of the women. Monroe may have been limited by lack of access to her main characters: Statman is guarded, Lee is deceased and another subject declined to be interviewed.

Most valuable is the moral nuance that Monroe brings to a genre that inspires fierce fandoms and disgusted dismissals but not enough scrutiny in between. She writes with clarity about the ways true crime distorts our vision, citing polls showing that most people, especially most women, believe that violence is on the rise when it’s approaching an all-time low. These fears can contribute to real attacks, especially against people of color. “Steeping in ominous stories can make people into threats themselves,” Monroe writes.

But Monroe sees no reason to apologize for her appetites. “My whole life, I’ve been sharing scary stories with other women,” she writes. “Part of the curriculum of growing up as a girl is to learn lessons about your vulnerability – if not from your parents, then from a culture that’s fascinated by wounded women. From an early age, women are primed to notice potential danger. … At its best, true crime is a recognition of this subterranean knowledge.”

We can feed the hungers that come from a place below reason, and we can also pay careful attention to where those hungers lead us. I’ll think of this the next time I hear someone describing with excessive pleasure a murder they heard about on a podcast. And that means I’m bound to think of “Savage Appetites” often, and soon.

– Reviewed by Nora Caplan-Bricker, who is a writer in Boston.