Book review: ‘Be Free or Die’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 11, 2017

- Book review: 'Be Free or Die'

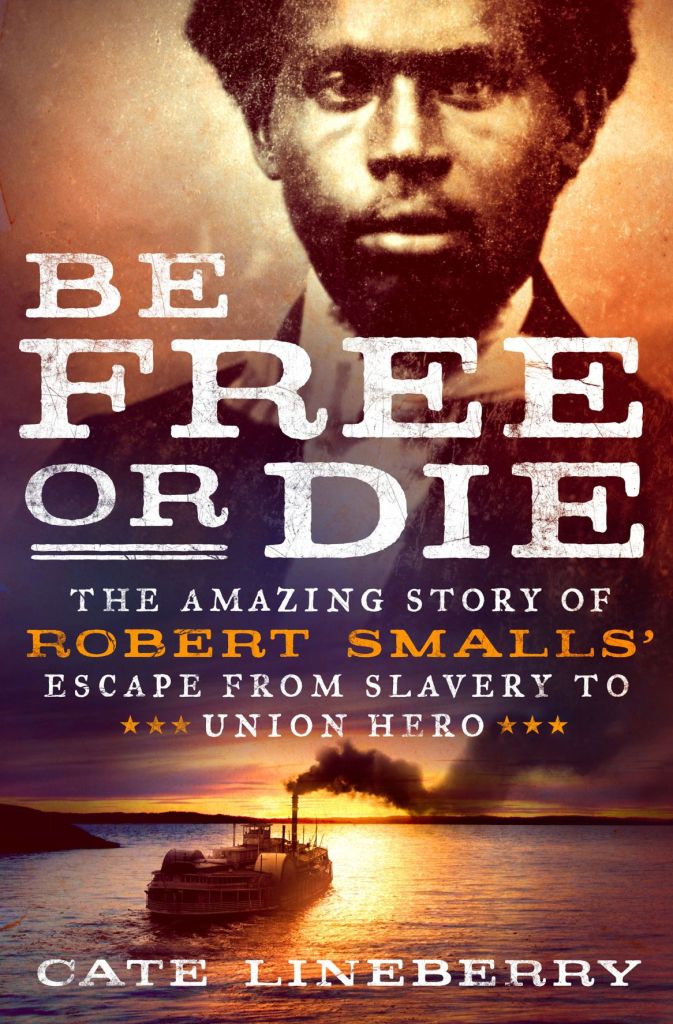

”Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero” by Cate Lineberry. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2017. 288 pages, $25.99 (hardcover).

The American Civil War continues to be among the most popular subjects for reading in U.S. history. However, the story of Robert Smalls’ shocking theft of the Confederate steamer “The Planter” from Charleston’s heavily-fortified harbor and surrender of the boat to the Yankee command besieging the harbor is one of the most exciting adventures and one of the best-kept secrets from that period.

Trending

Journalist Cate Lineberry has now addressed that deficiency with the publication of “Be Free or Die.” Lineberry is the author of “The Secret Rescue,” another historical thriller that recounts the amazing rescue of a group of American nurses and medics from behind Nazi lines in World War II. That exciting book earned her several award nominations, and this one should do the same. I can’t wait to see the movie version!

“Be Free or Die” opens with “The Escape,” a chapter describing how a 23-year-old slave managed to get into a position where he could steal the steamer in the first place. Smalls knew the waters of Charleston’s harbor very well, and the white crew of “The Planter” valued his skills and had promoted him from deckhand to wheelman.

As part of a crew of 10, including three white officers, Smalls had the knowledge and ability necessary to pilot the vessel, but planning a successful escape and keeping the plans quiet was a major challenge. The officers occasionally left the boat in charge of the seven enslaved black men overnight so they could spend time with their families in their homes. The officers likely believed that these men were not capable of stealing the boat and escaping Confederate guards and fortifications.

On May 13, 1862, the plot succeeded despite a series of threats. Smalls managed to fire up the steamer’s engine and move the boat away from the harbor’s entrance to pick up several family members without detection and then leave the harbor and sail beneath the well-fortified Forts Johnson and Sumter without incident. It helped that Smalls donned the captain’s familiar straw hat and that Confederate guards assumed that they were seeing the captain steering the steamer.

Smalls was able to signal with the boat whistle the appropriate sounds to secure freedom of passage. Perhaps the greatest threat was that the commanders of the Yankee ships patrolling outside Charleston would assume that “The Planter” was an enemy vessel attacking them. Smalls lowered the Confederate and South Carolina flags and hoisted up a white bed sheet, but increasing fog made this difficult to see. Although the Yankee captain at first ordered his men to target their cannon on “The Planter,” he saw the white flag in time to stop an attack. Smalls successfully delivered “The Planter” into Northern hands, including with the four giant cannon the steamer had been transporting the previous day.

In subsequent chapters, Lineberry explores Smalls’ life both before and subsequent to his courageous escape. When interviewed during the war, Smalls reflected on his experiences with slavery: “I have had no trouble with my owner but I have seen a good deal in travelling (cq) around on the plantations. I have seen stocks in which the people are confined from 24 to 48 hours. In whipping, a man is triced up to a tree and gets a hundred lashes from a raw hide. … My aunt was whipped so many a time until she has not the same skin she was born with.”

Trending

Smalls’ feat was naturally applauded in the North, where Yankees were desperate for any kind of victory. The New York Herald reported on the event: “One of the most daring and heroic adventures since the war was commenced was undertaken and successfully accomplished by a party of negroes in Charleston on Monday night last.” In Boston and Philadelphia, photographers sold portraits of Smalls alongside White House photographs. The Boston Evening Transcript published a poem honoring Smalls titled “Our Country Calls.” Some politicians in Washington suggested that the crew deserved prize money for delivering the vessel, even though they were not members of the military. A bill to authorize a reward passed the Senate unanimously and succeeded in the House by a vote of 121-9, though the Kentucky representatives walked out of the room in protest. President Abraham Lincoln signed the bill May 30, only 17 days after the event. Congress must have moved faster in those days!

In August 1862, Smalls and the Rev. Mansfield French went to Washington and met with Lincoln and several Cabinet members, including Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. They carried a letter from Gen. Rufus Saxton asking Stanton to authorize the recruitment of black troops. They were asked to carry back a dispatch to Saxton authorizing enlistment of black soldiers. During his trip Smalls also delivered his first public speech to a crowd of 1,200 in one of the largest black churches in the capital and gave other speeches in New York and Philadelphia. In 1863, Smalls’ only son died of smallpox at the tender age of 16 months. Near the end of that year, Smalls was named the civilian captain of “The Planter” at a salary close to that earned by a Union major. Early in 1865, after the Union forces occupied Charleston, Smalls piloted “The Planter” on its return voyage to the harbor.

In the post-war years, Smalls continued his work on “The Planter” and bought the house in Beaufort, S.C., where he and his mother had once served as slaves. Smalls was gracious toward his former owners, inviting them to visit and providing money for the family’s widowed daughter, as well as helping her son secure an appointment to the Naval Academy. Smalls became a founder of the Enterprise Railroad Company of Charleston, started a school for African-American children in Beaufort and joined the state militia, rising to the rank of major general in 1873.

From 1875 to 1887, Smalls served five terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and after that he was U.S. Customs collector for the Port of Beaufort. Although his life following his escape from slavery sounds very successful, it was not without its challenges. As an African-American and Republican politician living in South Carolina, Smalls received several death threats and had to defend himself in the courts against a trumped-up charge of receiving a bribe and a challenge to his house’s title. He was the only delegate to the South Carolina Constitutional Convention in 1895 who refused to sign a document that took away the right of blacks to vote and paved the way for other Jim Crow laws. Smalls died from complications of diabetes in 1915.

“Be Free or Die” provides fascinating insight into a little-known heroic incident of the Civil War and into race relationships in the Reconstruction South. The author captures very effectively the excitement and tension of the times and brings the key players to life very effectively. It is an excellent read for anyone interested in the period.

– Reviewed by Richard D. Weigel, Western Kentucky University History Department.