Book review: ‘Merton & the Protestant Tradition’

Published 12:00 am Sunday, June 4, 2017

- Book review: Merton

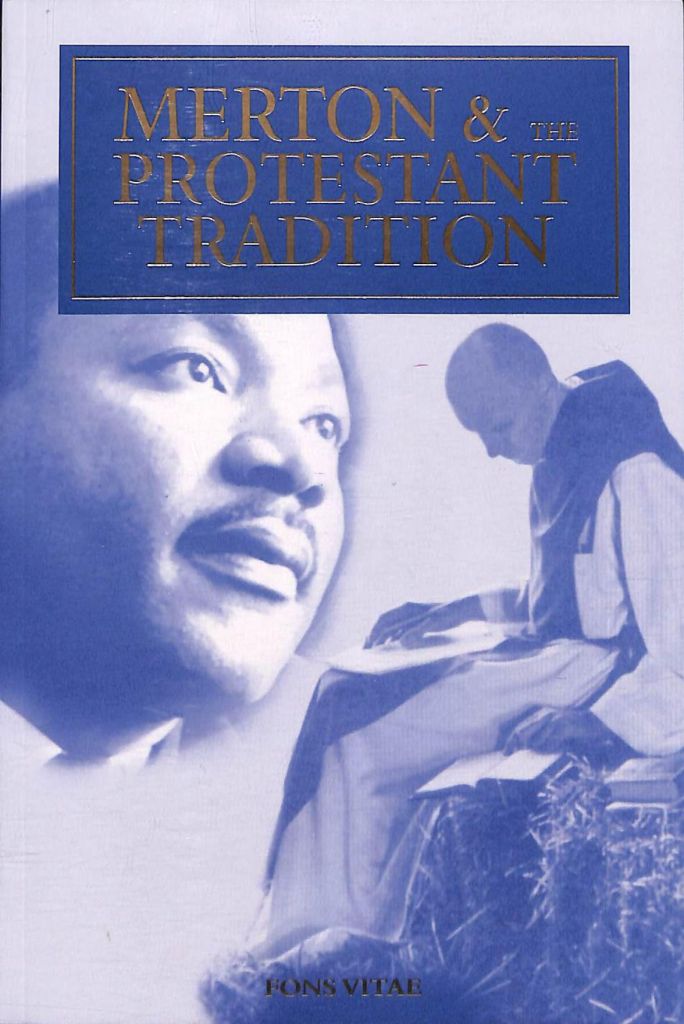

”Merton & the Protestant Tradition” edited by William Oliver Paulsell. Louisville: Fons Vitae, 2016. 200 pages, $25.95 (paperback).

The book “Merton & the Protestant Tradition” is about the intellectual and spiritual search for the meaning and purpose of Christianity in a pluralistic world. The American theologian Thomas Merton (1915-1968) stands out as a prolific author of 70 books and journals.

Merton attracts the attention of anyone living in the modern world who is interested in ways of establishing a lived understanding of Christianity. Otherwise, as stated below, Merton is one of many good Christian thinkers interested in the improvement of human conditions in the modern period. This group includes Karl Barth, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Paul Tillich and others, such as the Anglican Bishop of Woolich whose book “Honest to God” became a classic of arguing a case for a secular Christianity “freed from religious myth,” allowing the believer not to feel guilty about being modern and existential about God.

Merton was not convinced by the attempt to sell Christianity without raising the awareness of God’s transcendence. Briefly, although dead for almost five decades at the time of this book review, there is an “enduring presence of Thomas Merton,” says the University Distinguished Professor of History at Western Kentucky University, James Baker.

Baker explains his doctoral work. “I was doing more than summarizing and analyzing his thought. I was at the same time incorporating it into my own. What he had to say about racial justice and its social implication, what he had to say about the war and its consequences, what he had to say about the obligation of religion to take bold and often controversial stands on these issues … all these became the framework for my own social conscience.”

Merton thus seemed persistent in his quest for realistic ways of transcending the problems of suffering in a changing world in which there were different Christian traditions and religious folk more interested with what distinguished beliefs from each other. For Merton, the whole point of dialogue is to promote peace and justice among members of the same global society. Born to parents who moved to the U.S. during World War I, Merton also lived through World War II. He traveled far and wide, here in America, France and England where he trained in theology at Cambridge University. When Merton died from electric shock, he was in Bangkok, Thailand.

As Baker put it, Merton had found admirers in “the Buddhist East”, including the Dalai Lama. The other striking features of this book are the people visiting Merton at the Abbey of Gethsemane in Kentucky. Personal friends, religious leaders, academics and students came from all over. Visitors from Louisville Baptist Seminary, Asbury Theological Seminary and other places not far from the monastery, such as the Shakers, whom Merton admired for their celibacy and work ethic, were joined by admirers from other parts of the U.S. and Europe.

This book gives one example after another of Merton’s friends and all sorts of people intrigued by his personality, books, journals and letters showing that he was looking for an ecumenical basis for “doing” theology as a social critic. There are nine different authors of articles found in the book, “Merton & the Protestant Tradition.” They all have something interesting to say about his enduring presence among “separated and potentially alienating poles of Christian faith.”

Writing as the editor and author of the two major articles on Merton’s books, William Oliver Paulsell draws attention to Merton’s time at Gethsemane. It provided some of his happiest moments, especially in the woods and fields, but also with the novices. “There had been terrible moments. But good moments, too, with Protestants coming here,” Merton wrote. He was interested in honest dialogue between Protestants and Catholics. Be it about virtues of faith or the need for an ecumenical theology for peace, justice and religious tolerance in the world, Merton seemed to enjoy finding out what he liked as well as what he did not like about both his Catholic and the Protestant Tradition. Merton is said to have appreciated the “decisive point in the Reformation” insofar as “Martin Luther’s belief in fides sola, faith alone, led to his repudiation of monasticism.”

The formalistic monastic tradition leading to the Reformation aside, Merton agreed that it was sometimes frustrating to abide by the rules for monastic life at the Abbey in Gethsemane. Luther’s teaching had certainly introduced a spirit of renewal from which Catholic monks could learn. Merton wrote, “If we want to bring together what is divided we cannot do so by imposing one division upon another or absorbing one division into the other. But if we do this, the union is not Christian. It is political and doomed to further conflict. We must contain all divided worlds within ourselves and transcend them in Christ.”

By transcending divisions in Christ, Merton meant more than accepting the fact that people can hold strong differences of opinion. He tried to either find the common ground or explain his own viewpoint. For example, Merton regretted the rise of “separated brethren called Protestants” whose good cause led to the throwing away of the baby with the bathwater. How? By rejecting celibacy, Protestants undermined their own cause.

Merton wrote, “ … to argue against the vow of chastity is to argue against religion. … Marriage is a waste of time and energy” for Protestants called to the priesthood. Luther’s frustration produced “sterile devotionalism, attachment to trivial outward forms, forgetfulness of the essentials of the Christian faith, and obsession with accidentals.”

Although critical of some of the rules of the monastery, Merton cherished the freedom to develop his own thoughts about an understanding of God characterized by celibacy, monastic prayer, contemplation, reading the scriptures, and news about the world and writing. Merton regretted the lack of understanding of the monastic tradition by Protestants, and saw them as destroying religion, especially when it comes to celibacy.

Merton had learned from his travel in Europe that there was an ecumenical monastery in Taize, France – well known and appreciated by Protestants. Other Protestant monasteries were found in Germany and Switzerland. Closer to home in the U.S. there were Episcopal houses for both women and men where simplicity, openness and vitality were central monastic values appreciated by some Protestant churches.

The search for an ecumenical theology compatible with Merton’s own Catholic spirituality led him to develop an admiration for the Shakers. Founded in England, and eventually led by Mother Ann Lee, the Shakers founded several communities of men and women in America, including a group not far from Gethsemane in Kentucky. Shakers were known for their practice of celibacy, simplicity of life and craftsmanship. If Shakertown had survived it would have evolved as Gethsemane evolved. The women would now be driving tractors; the men would be advertising bread and cheese. “And all would have struggled with guilt.”

Alan Klop shows us yet more proof that the idea of a world torn apart by war and related problems, social change and immigration caused by the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights and Feminist Movements created the setting for Merton’s intellectual growth. Klop met Merton in the backyard of the Harvard Center for the Study of World Religions and was inspired by Merton’s dedication to global peace, love and justice, and the development of ecumenical God-Talk. Klop calls Merton a son and friend of the Quakers. Anyone who knows something about the Quaker interest in social justice will, by the time they get to page 161 of “Merton & The Protestant Tradition,” know why it makes perfect sense to ask a Quaker to strengthen the quality of a book concerned with Thomas Merton’s religious thought.

Given the diverse religions and cultures that comprise cities that are growing like Bowling Green, it is worth mentioning Eastern and Middle Eastern Religions. During Merton’s days at Columbia, he made friends with a Hindu monk. This is interesting because it was the asceticism of the Hindu monk which Merton liked, and thought Protestants undervalued by stressing faith alone.

Writing as an African scholar of religion and theology based in Bowling Green, it is not an exaggeration to say that among the readers of this article will be Muslims, Buddhists, the Baha’i, Wiccans, and many who could not care less about practicing any religion. What makes this book fascinating are the different voices of young readers of Merton. For instance, Justin Klassen was an undergraduate student at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia taking an introductory course on world religion when he came across Merton. Fraser contributes to the story of Merton and Protestant because he was drawn to the idea of “an integrated life” – one that differs from the Evangelical tendency to separate faith from the “binding process of transformation” by sweeping things under the carpet.”

Last, but not least, Merton took the trouble to look at the works of his contemporaries. Paulsell says Merton looked at all the leading Protestant theologians when he developed some knowledge as a student of theology, at Cambridge for instance. One of these was Karl Barth (1886-1968), a leading Protestant theologian who lived through World War II and was asked to leave his job for refusing to take an oath of allegiance to Adolf Hitler. Merton said Barth argued that Judaism and Christianity were sister religions whose sacred texts revealed the same God. On the horrors of anti-Semitism, Merton wrote, “Barth saw clearly that Nazi anti-Semitism was also an attack on Christ.”

Merton admired Barth enough to engage him as a fellow theologian who made the mistake of neglecting natural theology. In conclusion, it is not possible to finish the list of theology books read by Merton, and it is even more difficult to say how many more people liked or disliked the way he exercised his freedom of speech as a Catholic becoming so interested in building bridges with Protestants, and members of other religious traditions.

“Merton & the Protestant Tradition” presents readers with a rather serious intellectual challenge to do with knowing something about world religions and why they matter.

As an international scholar of religion and theology concerned with the deepening of questions about global warming, it is appropriate to end this book review by drawing attention to the need for innovative research on ecumenical conversations on new threats of nuclear war, violence, racism, sexism, poverty and climate change. I highly recommend this book to university students looking for way of making the study of religion and society life transforming.

– Reviewed by Bella Mukonyora, Department of Philosophy and Religion, Western Kentucky University.