Civil War opened wounds, caused rifts within local families

Published 4:45 pm Thursday, September 13, 2012

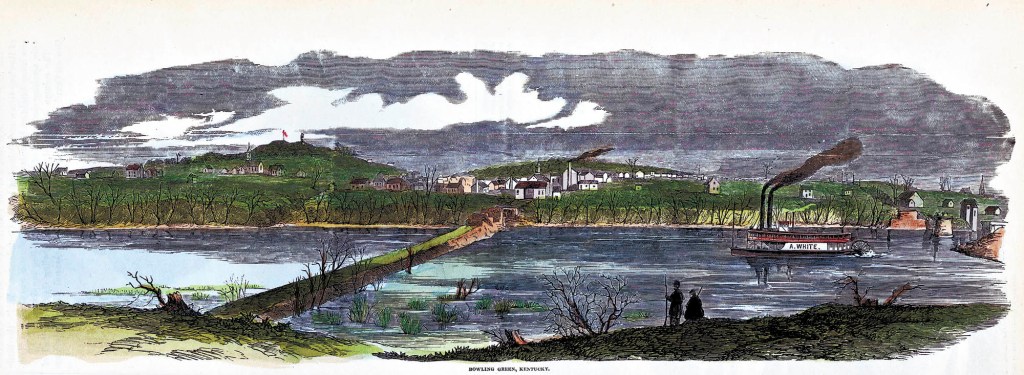

- Illustration from HarperÕs Pictorial History of the Civil War showing Bowling Green, KY, College Hill and fortification in the distance, Pike Bridge destroyed by the Rebels, Court House, and Railroad Bridge destroyed by the Rebels. circa 1862. (Photo Courtesy of Special Collections-WKU)

“The Philistines are upon us,” wrote Johanna Louisa “Josie” Underwood in her Bowling Green diary in 1861.

“It has come,” she writes Sept. 20, three days after the invasion. “Kentucky’s neutrality is over! On the morning of the 17th (Confederate Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar) Buckner, with his hosts of disloyal Kentuckians and other Rebel troops – rushed up by rail from Camp Boone and took possession of the town. Heavens! How I felt. I had never before realized that the Flag meant anything special to me – That I loved it. It was simply a pretty Banner pleasing to see waving in the breeze. But today – when I saw that Flag with drooping folds coming slowly down and that other run up quickly to flaunt gaily in its place – I verily believe, girl as I am, had I been in that crowd I could have shot the man who pulled that Old Flag down, and all day long and now – late at night my heart feels like it was washed in a strong, terrible grip, that will prevent its ever beating free again,” she poured out her emotions on the page.

Trending

Bowling Green residents had never experienced military occupation. And the Civil War, which put members of families on opposite sides, created greater wounds than just those suffered from cannon and gunfire.

Author Nancy Baird of Bowling Green said many local families had men serving on both sides of the war, fueling the emotions of the conflict – emotions that continued to energize debate even years later.

“If a father is on one side and a son is on the other side and the father loses a leg, how do you forgive?” Baird said. She added that the emotional aftermath of the Civil War was certainly unique in Kentucky, which was a Union state that also saw Confederate leaders designate Bowling Green as the Confederate capital of the state. The state’s Union-backed government continued in Frankfort simultaneously.

“That was much ado about nothing,” Baird said. “They met in Russellville and made the declaration in November, went home for Christmas, and by February they were gone.”

For tiny Bowling Green, the occupation of the community by the Confederate forces during the Civil War was “the most exciting event that had ever occurred in the countryside,” noted Elizabeth Coombs, Kentucky Library librarian, in “Union Occupation of Bowling Green,” a Civil War discussion she compiled in 1961.

Underwood, a fiery and opinionated 20-year-old, notes that a fort was built in the backyard of her home place, Mount Air, and the Underwoods were powerless to stop the rebels from cutting down trees on their property, stealing their Christmas dinner and even casually using a rocking chair in Lucy Underwood’s room while her ill mother attempted to recover in a nearby bed.

Trending

The Confederate captain continued rocking by the room’s fire while winter’s chill swirled outside the house, oblivious to the insensitivity he was displaying.

Underwood’s diary notes that the occupation of Mount Air turned the children there into reporters.

“The children, white and black, are on the lookout all the time and constitute themselves a gang of excited reporters – all day rushing in with one tale or another – the soljers are digging taters at the bottom of the garden. Theys got one of we’all’s pigs – ’cause it heard its squeal, and then the boys – go after them and can do nothing if they find it all true and we have told them we can’t help it all but we can’t stop the excitement that pervades everybody on the place,” she wrote.

The frustration is evident in her diary entries.

“How long, O Lord, how long?” Underwood writes, decrying the Confederate occupation in her diary.

She describes the energy that gripped the town when the rebels arrived Sept. 16, 1861.

“While I was there, the train from the South came in, mostly platform cars, whistles blowing, men yelling and more noise than I had before ever heard,” Underwood said of the scene on lower Main Street.

She was a Union sympathizer trapped in a Confederate world and none too happy about it.

“Thousands and thousands in gray uniforms and no uniforms at all. The space around the depot was filled with troops. An American flag was flying beautifully over the depot which the citizens of the town had hoisted there a few months before. They commenced shooting at the flag and continued doing so until it was riddled to tatters, then hauled it down and hoisted into place a new banner, the Stars and Bars.”

Confederate Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner took over command of 5,000 men and a battery of artillery in Bowling Green, Coombs notes.

Mount Air was on the northeastern fringe of Bowling Green. At that time, Bowling Green had 2,500 residents and Warren County’s population was 17,300, Baird notes in the introduction of “Josie Underwood’s Civil War Diary.”

It was – still is – the largest town between Louisville and Nashville.

Before the Civil War, the Underwoods were worth about $100,000 and owned 28 slaves, placing them among the county’s wealthiest residents, Baird notes. By the end of the war and beyond they were virtually penniless and the beauty of Mount Air was destroyed.

The Confederates would only occupy Bowling Green for five months. They fled southcentral Kentucky to support Confederate forces south of them defending against Union armies that were bearing down on the more strategically important Nashville. Once they left, the Confederates never occupied Bowling Green again.

During their stay, the number of soldiers grew to 25,000. Ten percent of them died not from bullets, but rather disease.

When they left five months later on Valentine’s Day in 1862, they destroyed the rail depot, the railroad bridge at College Street and the wooden foot bridge crossing the Barren River.

“This town is declared under Martial law,” wrote Confederate Maj. Gen. W.J. Hardee on Feb. 13, 1862, in a public pronouncement before the Confederates left Bowling Green.

“All citizens and soldiers except the guard, will retire from their quarters at 8 o’clock P.M. A strong force will be stationed in the town. All persons found in the street will be arrested. Anyone attempting to fire any building will be shot without trial,” Coombs notes in her history.

Hardee remained until the end to report to the Confederates that the Union had appeared at noon on Valentine’s Day on Baker’s Hill.

The Union proceeded to shell Bowling Green from across the Barren River before entering town.

Confederate Texas troops left their calling card – a torched rail depot and roundhouse.

“Local folks who rushed to greet the initial Federal troops were appalled to discover that their rescuers were not Kentuckians, but rather a group of hungry coarse Dutchmen,” Baird writes.

The Union commander, Col. Ivan V. Turchin, made little effort to control his troops. “Their looting and drunkenness was never forgotten,” Coombs writes in her history.

With a fairly new main rail line running through town from Louisville to Nashville – and a second, newer rail line veering off to Memphis – Bowling Green was a strategic chess piece in the war between the states.

And it wasn’t just the L&N Railroad, said Sharon Tabor, director of the Historic RailPark and Train Museum in Bowling Green. Those critical transportation arteries that both the Union and the Confederacy wanted included a stagecoach line and commercial freight traffic on the Barren River. Bowling Green was also accessible from the Ohio River on a steamboat by way of the Green River.

“No other railroad passed through both Confederate and Union territory,” Tabor said. “The L&N was a major supply line during the Civil War.”

There were five hills at that time in Bowling Green upon which military forts could be placed, according to information on the visitbgky.com website.

Ironically, the Union army had determined the military importance of Bowling Green early on, but by the time they got ready to move on the Warren County community and transfer a camp from Jeffersonville to Bowling Green, the Confederate troops were already in Bowling Green.

Jack Thacker, senior history professor at Western Kentucky University, said President Abraham Lincoln understood Kentucky’s importance better than his generals did, and did not want to turn Kentucky against the Union by invading first.

“To lose Kentucky is nearly the same to lose the whole game,” Lincoln wrote to a friend. “With Kentucky gone, we cannot hold Missouri nor, I think, Maryland. These (are) all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us.”

The first regular L&N train between Louisville and Nashville made the trip Oct. 31, 1859, and the Memphis branch had only established rail service between Louisville and Memphis on April 14, 1861 – just two days after the Confederates fired on Fort Sumpter in South Carolina, Coombs wrote in her history.

Once the Civil War ended, Bowling Green was disease-filled, penniless and decimated.

The rebel occupation had been the crescendo of the war anxiety.

“It was a great shock to the townspeople when they learned that the entire army encamped in the vicinity of Bowling Green was being moved out as rapidly as possible, but also a relief to know that a battle would not take place here,” Coombs writes.