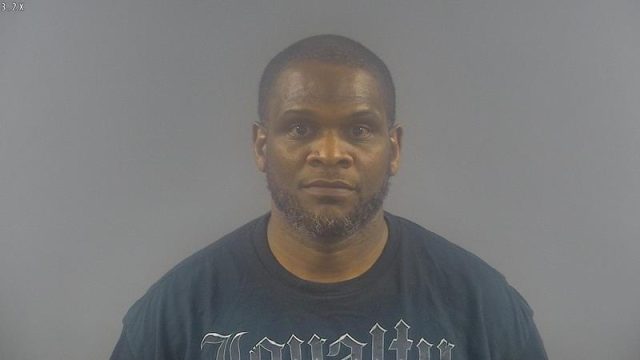

Scott gets year

Published 12:00 am Friday, July 7, 2006

- Richard Lord, a 14-year member of The Presbyterian Church at 1003 State Street, paints the wrought iron fence this morning around the church. Photo by Joe Imel

A Bowling Green businessman was sentenced to a year and a day in federal prison Thursday for intentionally understating his income by nearly $1 million on tax returns.

The attorneys for James D. Scott, 68, while successful in getting a reduction in the 15-month sentence recommended by the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Louisville, didn’t convince U.S. District Judge Thomas Russell to sentence Scott to a fine, community service and home incarceration in lieu of prison.

Trending

Scott was indicted in November 2004, according to court records. The case was delayed two years as Scott’s attorney challenged IRS investigation methods.

Scott, entered a guilty plea to four counts of tax fraud March 20. He intentionally signed federal income tax reports in 1995 and 1996 in which he knowingly understated his income, according to the plea.

Federal court documents state that Scott understated his income by $986,645 – money spent to construct his house in Rivergreen that was paid by his company.

Scott will have a year of supervised release after serving his sentence. Scott’s attorney, Scott Cox of Louisville, spoke of his client’s philanthropy and the need to be available to help care for his adult son, Tony, who suffered significant brain damage after an accident years ago, as reasons against prison.

Scott has paid about $3 million in back taxes, interest and penalties to the IRS, Cox said.

Several community members spoke on Scott’s behalf and more wrote letters to Russell requesting leniency.

Trending

Scott did a lot of work for underprivileged children in this community, Cox said. The criminal behavior is an aberration, he said.

“He’s already been punished significantly,” Cox said. “He’s totally and completely humiliated by what happened.”

Tax-related cases are normally about greed, said James Lesousky, assistant U.S. attorney.

“He thumbed his nose at the IRS and its rules,” Lesousky said. “It wasn’t that he couldn’t afford to pay the IRS; he easily could.”

His community activities weren’t something James Scott considered when he rolled the dice and engaged in behavior that could land him in prison, Lesousky said.

Scott has the resources to ensure his son and all his family are cared for while he serves time, the assistant U.S. attorney said. Defendants with family issues are sentenced to prison routinely who don’t have that ability.

Western Kentucky University President Gary Ransdell was the first to testify during the sentencing hearing in U.S. District Court in Bowling Green.

Scott has been a major donor to the university, as well as helping with its fundraising efforts, Ransdell said.

“He’s been called on many times for his tangible support and intangible leadership,” Ransdell said.

Scott was involved in the creation of Western’s engineering program and has been a driving force for economic growth in the area, Ransdell said. Scott’s $1 million donation to the civil engineering program created Western’s only fully funded endowed chair in the university’s history.

Scott was also a supporter of Western athletics, public radio and television, arts and other programs, Ransdell said.

Olde Stone, a planned community and golf course development on Scottsville Road, is also something that will provide a quality of life that has not existed in this region or possible the state, he said. The project’s economic impact has not yet been realized, he said.

Scott has been active in the community since he started his business in 1974, said Johnny Webb, former Bowling Green mayor. Scott participated in a number of charity efforts people didn’t know about, he said.

He has donated more than $1.5 million to Western and contracting services and money to groups such as The Salvation Army, Boys and Girls Club, Commonwealth Free Health Clinic and Girls Inc.

“He’s always been very giving and generous,” Webb said.

Scott would come across the tracks and be involved with the kids at the Boys and Girls Club, which a lot of other people would not do, said Stan England, who was executive director of the Bowling Green club for 25 years.

“He’s helped many kids,” England said. “He wants to give people an opportunity.”

Scott would create activities for his son, Tony, and try to get him involved in business ventures, said Lawrence White, a former business partner of Scott’s in Scott Waste Services, which is now owned by an outside company.

“Most of the time it was like dealing with a young teenager,” White testified about Tony. “He tries hard, but he’s someone you have to have certain reins on.”

Tony Scott had the figurehead title of company president, but reported to someone with a lower title, White said.

James Scott would call his son at least twice a day to check on him and call White at least once, he said. It would be detrimental to Tony Scott if his father was in prison because he needs someone to oversee him every day.

Tony Scott isn’t capable of running a business without his father’s help, Webb said.

James Scott has been responsible for taking care of his son since the 1980 accident, said Mike Murphy, a former business partner of James Scott.

“You’d be surprised at what he could do, but not on a consistent basis,” Murphy said, referring to Tony Scott. “When he’s not with his dad, it’s unbelievable what could happen.”

Webb, White, England and Murphy all testified that James Scott is the only person who can keep his son under control.

“I don’t think Billy Graham and Walker, Texas Ranger could control him,” England said.

His father is the only person Tony respects and listens to, England said.

“We were disappointed in the decision,” Cox said after the sentencing. “But we respect Judge Russell’s decision.”

James Scott will surrender to U.S. Marshals in the next six to eight weeks to begin serving his sentence, Cox said. He will actually serve between eight and 10 months in custody, with credit for good time served, he said.

Russell agreed to recommend that James Scott serve his time at the Federal Correctional Institute in Manchester, a medium security facility in eastern Kentucky.